Walking the Walk: Christie Walk’s bold strides towards urban sustainability

“Cities are our most magnificent creations, but are essentially physical, built expressions of the society which creates them and, like all societies, they require constant maintenance to operate. Life is about maintenance and sustainability is nothing if it’s not about life.” – Paul Downton, Christie Walk

We all know that cities are in need of radical change, it seems that progress is coming largely from the ground. Since 1999, the inner-city sustainability exemplar par excellence Christie Walk is leading by example, and proving that citizens can outpace government when it comes to forging bold new directions towards social and environmental wellbeing.

The rise of the urban human

Eighty-five percent of Australian people live in cities. For the most part, Australian cities are well-planned and equipped with the necessary infrastructure to meet most needs (though access to housing is a major concern and food prices, as elsewhere, continue to rise). However, overwhelmingly, planning has not included sustainability. The word only entered the urban planning lexicon in recent years, as we’ve recognised that our city systems are wasteful, inefficient and leave a colossal ecological footprint.

Changing these systems is not only complex, overwhelming and no doubt expensive; at once, they confront institutionalised attitudes of ‘development’ and consumerist fashions, and may cost jobs. Governments and councils seem reluctant to display the necessary boldness.

That said, it must be noted that Australian building codes are beginning to encompass sustainability concerns. Recently we have seen rainwater tanks made compulsory and greater emphasis placed on solar panels and energy efficiency. However change is slow, especially when corporate interests are stake.

The revolution will be strawbale

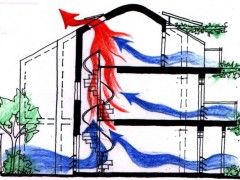

Finalist in the 2005 World Habitat Awards, Christie Walk is home to around 40 people. The cottages, apartments and townhouses within defy conventional design; not only are the homes colourful but they halve energy and water consumption. Made of straw-bale, r ecycled timber and ‘earthcrete’, they utilise thermal design, insulation, double glaze windows, ventilation and vegetation to abolish the need for air-conditioning, even in Adelaide’s 40˚C + summer heat.

ecycled timber and ‘earthcrete’, they utilise thermal design, insulation, double glaze windows, ventilation and vegetation to abolish the need for air-conditioning, even in Adelaide’s 40˚C + summer heat.

Moreover, the designs are in tune with the surrounding environment; factors such as how the sun moves and the air flows form integral parts of the architectural design. Grey-water is recycled on-site and used to water the vegetable gardens, while windmills and solar panels generate energy.

Interestingly, and somewhat surprisingly, creating this visionary place has been largely free from legislative barriers. With approval from engineers where required, these eco-friendly materials were good to go. The primary obstacle was the regulatory insistence on car parks and the laundry space, grounded on the individualist assumption of individual ownership and car-centric mentalities – factors that architect Paul Downtown was aiming to minimise. With some persuasion, the car-park requirements were waived.

Downton’s primary obstacles came from the corporate sector; a reluctance to engage with new ideas for fear of liability, insurance and, arguably, comfort zones. This corporate reluctance to experiment is often what prevents forward-thinking groups from building their green homes.

Christie Walk is not alone. It is part of a much bigger picture of forward thinking and meaningful action. Food Connect for example works across Australia connecting urban citizens with local organic farmers to provide healthy and affordable sustenance and reinvigorate lost relationships between farmer and city-consumer. Likewise, numerous farmer markets and urban community gardens have been set up across Australia and ‘eco-villages’ and permaculture communities are becoming more and more common. It is developments like these that evidence that new ways of being, that do not compromise our standard of living but do revitalise lost values of community while creatively reducing our ecological footprints are within our reach.