In Defense of Green Protectionism: Why the EU should put the planet before free trade

EU Climate Commissioner attempts to persuade partners at the Durban summit in December. (Credit: European Commission)

There is perhaps no area where interdependence and the futility of a strictly national approach are clearer than on the environment. Whether we’re talking about shrinking stocks of over-consumed fish, rising air pollution or the radioactive particles from a nuclear accident, national boundaries offer no protection. This reality is at the core of the 2012 Earth Summit: To bring governments together to reach common strategies and commitments to shared environmental problems.

Yet often this approach fails. What if there is no agreement to be found or, if it is reached, it is so watered down by the need to find accord between disparate countries as to be rendered meaningless?

The most famous global environmental agreement of all was victim of this. The Kyoto Protocol, which aims to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, was signed in 1997 but only entered into force in 2005, because it could only take effect if countries cover 55% of global emissions were covered. The United States of America, until recently the world’s biggest emitter, remains outside of its purview.

There are ways of attempting to move forward with smaller “coalitions of the willing”. Perhaps most ambitious multinational attempt at fighting climate change is the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), the largest cap-and-trade carbon system in the world, which effectively works as a kind of “carbon tax” for industries under its rules (mainly energy).

“Trade war” over carbon

The system, already controversial, became a source of international tensions when on 1 January 2012 the EU included the airline sector inside it. This would mean that airlines – a small but fast-growing part of emissions – would have to pay a carbon tax for flights both within the EU and flights with either departure or destination within the EU, also affecting non-European airlines.

This prompted an incredible show of opposition and unity against Europe, including that of the United States of America, Russia, India and China, to the extent that one Brussels media went so far as to describe it as signs of an emerging “trade war”.

The reason for this opposition is not based on the economic cost. The carbon price for airlines will be €8 per ton of CO2 emitted, which would mean a niggardly €2 for a flight from Paris to New York (not even a 1% price increase on standard tickets). The real issue is the precedent: For the first time, it would have meant that an environmental concern will have been given priority over free trade.

This raises all the fears of the international business class regarding protectionism, typically expressed in a recent article in The Economist attacking France and the European Commission for advocating “reciprocity” in trade relations (e.g., that the EU only open up its markets to the extent that other countries open there).

The question for environmentalists is: When there is no agreement forthcoming, is there any real alternative to green protectionism?

Gearing up for a fight

The reaction of the world’s other economic giants to the EU’s initiative illustrates another rarely-remarked upon reality: The environmental policy does not exist in a power vacuum but in a world of competing countries each looking out for number one. Environmentally-conscious countries cannot simply be virtuous in isolation, but will have to engage in a peaceful, global struggle with heavy polluters.

The Europeans have no right to lecture the Chinese or Indians on anything in this respect. Europe got a head start at polluting for almost 200 years with the Industrial Revolution and per capita carbon emissions in Asia are still far, far below those in the West.

However, Western Europeans do have rather more moral authority in dealing with other developed countries, notably the United States, Russia, Canada and Australia. These are settler-nations who, because of their vast size and plentiful energy resources, have no tradition efficient energy use.

The case of the U.S. is flagrant as a land of inefficient heating, fridge-like air conditioning, universal SUVs and other gas-guzzling vehicles, long commutes, urban gridlock and suburban sprawl. Not only does the country not invest in public transport, their use is often actively discouraged, as is the case with the stigmatization of buses in many cities as being only for minorities and non-respectable poor.

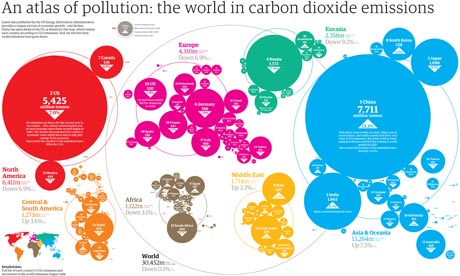

The result is massive, gratuitously high emissions levels (see the Guardian‘s graphic carbon atlas). The European Union has a larger economy and 200 million more people than the United States, but it emits around 20% less emissions. Similarly, Russia emits slightly more per capita than the EU, despite having a significantly lower level of wealth.

Exporting the European model

Europe, it so happens, pollutes relatively little for a continent of its wealth. This is not so much due to any particular environmentalist virtue on the part of European citizens, but rather the fruit of its history, as a densely populated, largely resource-poor continent, and one which in the 1970s and 1980s, was subject to extremely high energy dependence on politically unreliable sources in the Mideast and the communist Soviet Union. As a result, Europeans have enacted public policies in transport, gas taxes, and other areas to make them as energy independent and efficient as possible, and these have paid off over the decades. (Japan is also a relative low-polluter for very similar reasons.)

Europe has every right to export this energy model to other developed countries, forcefully if necessary. It should stand up at accurately price carbon in airlines as well as areas, such as oil taken from Canada’s tar sands, even if it means conflict with Ottawa.

Europeans also, by their economic power, have the means to assert themselves. The EU, even with its current economic troubles, remains by far the largest economy in the world by nominal GDP (which most accurately reflects an economy’s weight in the world economy and trade), representing a full quarter of the global economy. In 2011, according to IMF figures, the EU economy was over 15% larger than the United States’ and two-and-a-half times larger than China’s. In addition, on the Western Eurasian landmass, which is to say in Europe’s relations with the former Soviet Union, the Middle East and Africa, the EU’s trade position is so dominant that it can effectively impose its preferences in that region.

International environmental policy should meet power politics. If strong agreements on environmental issues prove elusive, environmentally-conscious countries should not hesitate to band together and pressure others with green protectionism.

Tags: CLIMATE CHANGE, Earth Day, European Union, green protectionism