The resurgence of terrorism in Peru

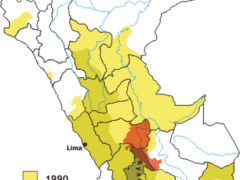

Areas where the Shining Path was active in Peru. Photo from Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

During the 1980s and 90′, Peru was plagued by terrorism, mainly by the Shining Path and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) groups, but also – and to an extent never clearly determined – by human rights violations in which the various governments dealing with terrorism were complicit.

In 1992, after the arrest of Abimael Guzmán, the leader of Shining Path, the organization went into decline and received another blow with the arrest of Óscar Ramírez in 1999. For its part, the MRTA wound down action after the arrest of its leader Víctor Polay in 1992 and the death of his successor Néstor Cerpa Cartolini in 1996 during the storming of Japanese embassy by the MRTA.

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), between 1980 and 2000, 69,280 people died or went missing as a result of terrorism. However, these statistics have been vigourously contested [es] by various political groups and there’s still no agreement on them just as there’s no consensus on the work of the TRC [es] itself either – which somehow proves that the wounds caused by years of terrorism haven’t healed properly and that closure is still a long way off.

Yuyanapaq: To remember. CVR´s photographic exhibition. From The Advocacy Project´s Flickr page. Published under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

In any case, although government propaganda has always insisted that terrorism is over and has presented the occasional attacks during the intervening period as “narcoterrorism”, probably in an attempt to reassure the population and not scare away foreign investors, the actual reality has been a little bit different.

Take, for example, the case of the VRAE (Apurimac and Ene River Valley) area, a bastion for the remaining members of the Shining Path and a place they could move around freely. The leader of this army was a certain Comrade Artemio who was arrested in February 2012.

Despite this setback, the presence of terrorist elements hasn’t decreased in the area which nowadays, with the fight against the illegal trade in drugs, is known as VRAEM [es] because the Mantaro Valley with its many coco plantations has been included in the militarized zone.

2009 saw the creation of the Movement for Amnesty and Fundamental Rights ( (MOVADEF), an organization regarded as a cover for the Shining Path that has been linked to the resurgence of terrorism. In January 2012 it tried to register as a political party but finally gave up the attempt [es]. Even so, it is still active. Recently a meeting of the MOVADEF in Ayacucho was reported and it looks like they haven’t ruled out a return to armed struggle.

One of the more surprising things about MOVADEF are the numbers of young people who sympathize with their ideological line known as “Marxism-Leninism-Maoism-Gonzalo Thought” (Abimael Guzmán’s nickname was “Presidente Gonzalo”). There are some revealing indicators. Firstly, the growing presence [es] of the Shining Path or MOVADEF at universities in Lima and at other universities [es] across the country. Secondly, the lack of historical memory about the years of terrorism as if the most of the country prefers to forget about what happened.

One organization which could well be operating as a wing of Shining Path is the CONARE-SUTEP (National Committee for the Reorientation and Reconstruction of the Single Union of Peruvian Education Workers), a teachers’ union originating in the SUTEP [es] which for the past 40 years has represented teachers in Peru and initiated many strikes and protests. A recent journalists report [es] indicates that CONARE-SUTEP may have been divided into two factions linked to the Shining Path.

On the other hand, we also witness the situation of various Shining Path leaders convicted of terrorism [es] who will be released after serving their sentences in the coming months and years. One of the most prominent cases is the Shining Path’s number 2 official, Osmán Morote, who will serve out his sentence in June 2013.

All of these factors combined make the resurgence of terrorism a matter of serious concern for the whole of society. Furthermore, despite robust economic growth, the conditions which spawned these movements in the first place, such as poverty [es] and deep social inequality [es], still continue to exist, especially in remote rural communities in the mountain and on the outskirts of the major coastal cities. And they continue to fuel disatisfaction among many sectors of the population.

Neither does it help that younger generations are largely ignorant [es] about what happened during the years of terrorism and so are an easy prey for the smooth recruitment talk. The state and civil society must join together in curbing the growth of terrorism on all fronts, mainly on the political side [es], but also by agreeing on legislation [es] that squarely faces the threat posed by a resurgence of terrorism. Will Peru’s fragile democracy be mature enough to cope with a new terrorist attack or some extreme political positions in the democratic spectrum? Only time will tell, but don’t place your bets yet.

Translated from the Spanish by Miguel Ángel Ruiz Subires.