Can Private Education Increase Enrolment and Completion Rates Among Africa’s Youth?

On July 3, Pearson, a UK textbook company, announced its launch of a £10 million (approximately 15.4 million USD, 12.7 million Euros) fund directed at affordable education for children from low-income households in Ghana.

However, NGOs (non-governmental organizations) question whether it will improve school attendance, as many focus on raising enrollment and attendance rates among in government-funded schools. Sir Michael Barber, former education adviser for the former UK prime minister, Tony Blair, currently serves as Pearson’s chief education adviser and chairman of the new fund.

The first investment from the new fund is a stake in Omega schools, a chain of affordable, for-profit schools in Ghana, founded by Ghanaian entrepreneur, Ken Donkoh, and Professor James Toole of Newcastle University in the UK. In less than two years, Omega has expanded to ten schools and 6000 students. Professor James Tooley, a professor of education policy, is also an advocate of low-cost private schools.

Pearson’s investment will enable Omega Schools to expand beyond Ghana’s capital city, Accra. This expansion could mean Omega Schools would provide low-cost private education to tens of thousands of Ghanaian primary and secondary students. Additionally, Pearson has a pre-existing stake in Bridge International Academies, a chain of low-cost private schools in Kenya.

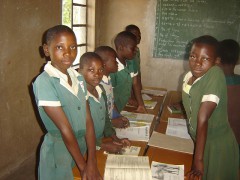

In response, several NGOs have questioned whether Pearson’s investments would help meet the UN Millennium Development Goal (MDG) on universal primary education. David Archer, program development head at ActionAid, made note of a the increase in primary school enrollment and attendance in Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda that followed the abolition of school fees in the late 1990s. Specifically, in Ghana’s most underdeveloped and underserved regions, school enrolment surged from 4.2 million to 5.4 million between 2004 and 2005 following the abolition of school fees (here, school fees must be distinguished from school tuition, which was banned 50 years ago).

According UN data, in sub-Saharan Africa school fees can account for up to 25 percent of a poor family’s income. Additional costs of school enrollment include meals, transportation, textbooks, uniforms, memberships in parent-teacher associations, and general community contributions. Cost-prohibitive school fees have a disproportionate on girls’ primary school enrollment and completion rates. Peninah Mlama, Executive Director of the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE), stated: ‘A lot of girls are dropping out of school or not being sent at all because of the poverty of parents. Traditional cultural attitudes are still very strong, especially in rural areas. The little money parents have to scrounge for sending children to school is seen as too big an investment to risk on the girl child’.

Generally, the abolition of school fees has meant that more girls were able to attend school. In Uganda, the abolition of school fees resulted in an immediate 20 percent increase in girls’ enrollment overall, increasing from 46 percent to 82 percent among the poorest one-fifth of girls.

With this in mind, we have to ask whether private investments (such as Pearson’s) in for-profit schools that charge fees will do anything to help raise school enrollment and transition rates between primary and secondary school among girls across Africa.

Tags: Accra, ActionAid, Africa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, ghana, James Tooley, Michael Barber, Pearson