Chinese Mining Company Displacing 527 Ghanaian Small-holder Farmers

In light of the Great Land Rush, that the Lead Article alludes to, smaller stories are often overshadowed. The narrative often includes players such as multinational corporations, governments, local traditional authorities and the displaced small farmer. The picture is of a lone widen-faced farmer who suddenly finds that their informal, customary land use rights are superseded by legal titles and contracts. It’s not simply that story. What’s often left out of the story is the resistance of smallholder farmers and their communities, whose livelihoods are entrenched in the land.

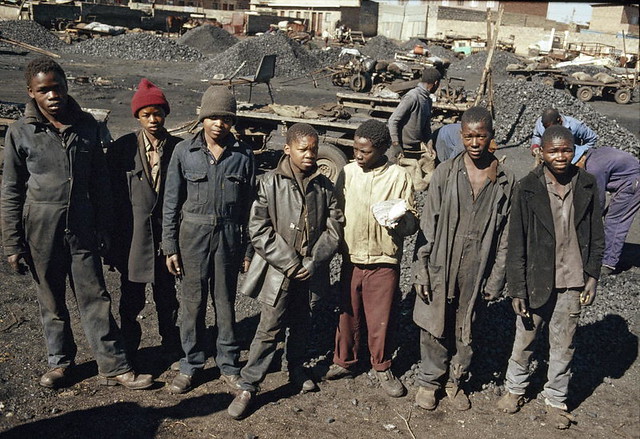

Shaanxi Mining Company Limited, a subsidiary of China Gold Resources Group Company Limited has destroyed over 3000 shea nut trees, an essential livelihood for Gbane Community in the Talensi-Nabdam District of Ghana’s Upper East Region. Additionally, the contract between the company and those who hold the title to the land allows for the displacement of hundreds of farmers in the area. This was reported in Ghana Business News on 6 June 2012, shortly after 12 individuals, including Galamsey assemblyman Bismark Zumah were arrested for vandalizing and setting about 3.5 million USD worth of Shaanxi Mining Company Limited’s property. They were later arraigned in court. Around this time, the Ghanaian government also posted a brief on its website, about the bridge that Shaanxi Mining Company Ltd is building for Gbane Community.

The history of legal and customary land rights in Ghana is complicated. Under Kwame Nkrumah, African socialism did not apply to land governance. Maintaining the colonial arrangement, lands in Ghana’s southern forest belt continued to be owned and controlled by Akan chiefs, while in the north, the land belonged to the state. Post-independence, CPP government sought to undermine the power of chieftaincies, but did not reform the underlying structures in regard to land claims and relations. Through taxation of revenues collected on land sales, rents and concession fees, the CPP government exercised its political muscles over the Akan chiefs. In February 1966, Nkrumah was ousted in a military coup led by Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka, after which Kofi Abrefa Busia, a member the Ashanti Confederacy Legislative Council, a seat of chiefly power in Ghana (it must be noted that the Ashanti are an Akan people).

Land rights continue to be a salient issue in Ghana. Land rights are still polarized between customary land owned by clans or chieftainships, and public land owned by the President. In both cases, land is vested in an authority for public use. Even legal instruments such as deed and title registration can be imprecise and cumbersome in terms of establishing rights and ownership.

Additionally, while customary law grants each person “usufructuary right of access to land of his or her community,” discrimination in terms of Ghanaian women’s access to land presents when women’s marital residence, overall land scarcity and gendered divisions of labor and food production are factored in both patrilineal and matrilineal areas. Even when women are granted customary rights to land, they have access to relatively smaller plots of land than their male counterparts. To quote a report entitled “Governance, Land Rights and Access to Land in Ghana– A Development Perspective on Gender Equity”:

“To a large extent, women’s access and control over productive resources including land are determined by male-centred kinship institutions and authority structures, which tend to restrict women’s land rights in favour of men.”

This gender bias especially affects women who are small farmers when land deals like the one in the Talensi-Nabdam District of Ghana’s Upper East Region displace previous inhabitants.

I write this to encourage a more well-rounded discussion of land within the context of increased investment in the world’s remaining arable land. Without factoring in the underpinning issues relating to access to land and land use, we only have a one-sided story of external actors displacing smallholder and subsistence farmers across Africa. This short piece illustrates that it is a multi-faceted issue.

Tags: Africa, Akan, Ashanti, China in Ghana, ghana