Generation Screwed: Why There Are No Jobs for Young People

Young people in the “wealthy” countries of the world are increasingly coming of age only to find there is no decent work for them.

The decline of the media industry and the business practices of innovative IT giants like Apple showcase how globalization and new technologies, while likely increasing overall wealth, are also leading to a generation of financially dependent “adulescent” youth for whom achieving a secure working or middle class existence is an increasingly unreachable dream.

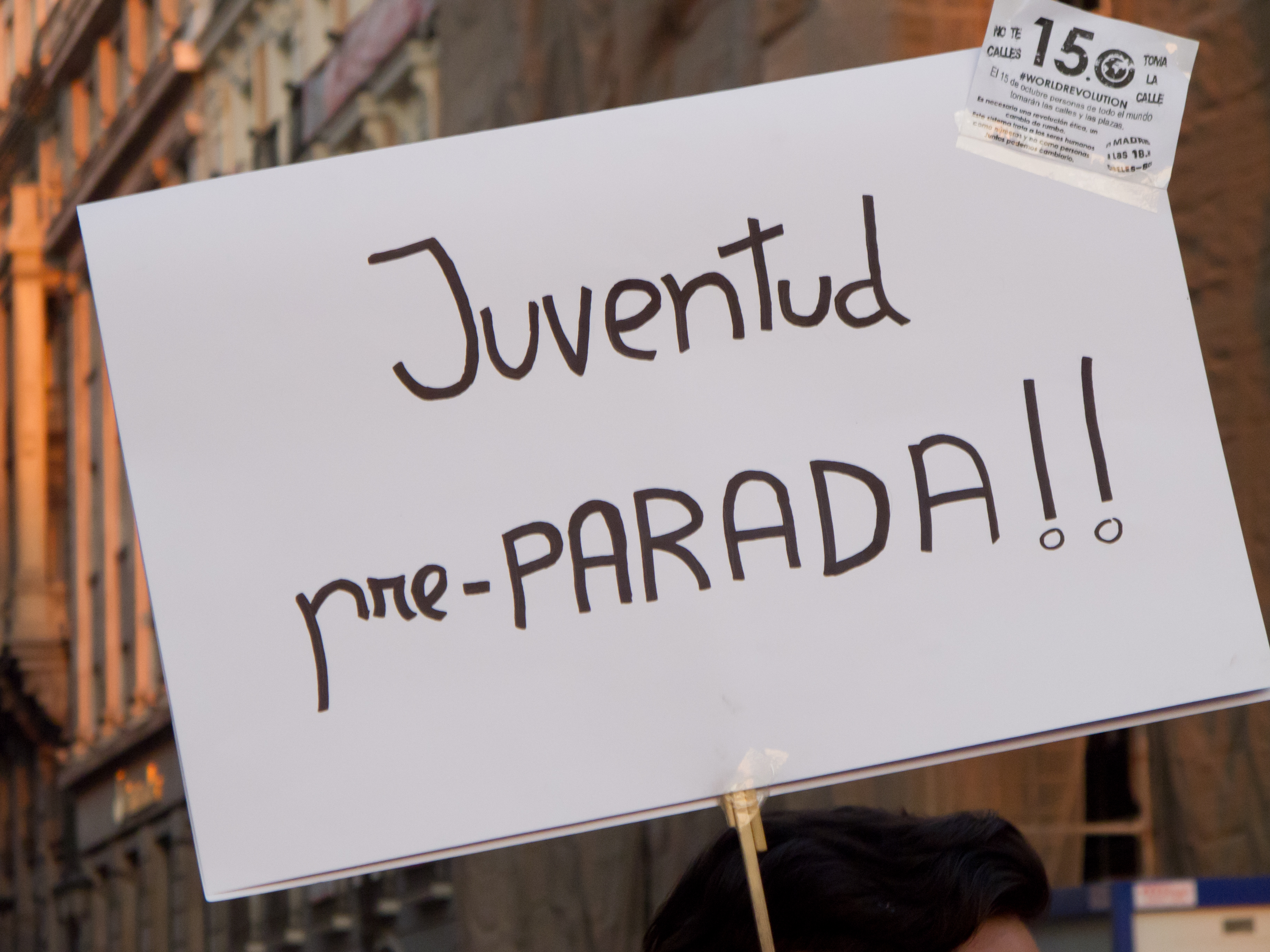

Spanish humor: Protest sign against youth unemployment in Spain with the pun “prepared/pre-unemployed youth.” (Kadellar – CC BY-SA 3.0)

All across the otherwise privileged countries of the “developed world,” young people are facing a dispiriting paradox: While they are the most educated generation to have ever come on the marketplace, they are also that with among worst prospects in terms of finding decent employment or even employment at all. For the first time in generations, it has become increasingly normal for parents to believe their children will be worse off than they are.

In the European Union, the irresponsibility and bankruptcy of politically leaders is captured in one simple statistic: 22.8% of young people are unemployed. In the United States of America, the figure is only somewhat better at 15.5%. These figures mask the fact that large numbers of “not unemployed” young people are actually in a semi-perpetual limbo of education and poorly paid “inadequate” jobs.

This is leading to strange and confusing situations for both young adults and their parents. Perhaps the most obvious problem is that young adults, being unable to find decent work, are also unable to achieve the financial independence that is the basis of adulthood, and so must still rely on their parents and float through an awkward “adulescence.”

In the English-speaking countries, there has been a steady increase in 24-34 year olds who, after a bout away from home to work or study, end up returning to their parents home, a phenomenon known as the “Boomerang Generation.” In France, a similar development has been termed the “Tanguy Phenomenon,” named after a 2001 film about a lame 28 year old who still lives with his parents. The Japanese, with brutal candor, term the twenty- and thirty-somethings still living with their parents “parasite singles”…

The phenomenon has different pathologies specific to each country. In the U.S., in addition to poor job prospects, young people are saddled with student loans that are continuing to drive Americans’ massive indebtedness. They now amount to a staggering average of $24,300 per person ($902 billion total). In Europe, the incoherence of the eurozone means youth unemployment diverges wildly by region, from “only” 8% in Germany and about 10% in the Netherlands and Austria, to 35% in Italy, Ireland and Portugal, and 54-56% in Spain and Greece (which is to say in some European countries it is reaching levels which normally lead to political revolutions). If anything the European figures especially understate matters because they don’t count people who choose to use their joblessness “productively” by seeking yet more education and training.

Though the specific dysfunctions and tensions appear different in each country, the causes are fundamentally the same everywhere, which is why no developed country has really been able to address the problem. The causes can be summarized by the problems posed by technological unemployment and rootless corporations in the context of economic globalization.

Technological unemployment: The case of media

As technology develops, human labor becomes increasingly worthless as machines replace them. So first the tractor made the farmer obsolete, then rising automation (and competition from the former “Third World”) made the industrial worker obsolete, now, finally, the computer has made so many paper-pushing office-dwellers (corporate and government bureaucrats) obsolete. Of course we never need no farmers, no workers and no bureaucrats, but with each innovation we need far, far less until the number needed is far less than the number of job-seekers.

The most obvious manifestation of this has been the ongoing collapse of the media industry and in particular newspapers. The point isn’t just that paper is gone (Newsweek, after having been taken over by the Daily Beast website some time ago, recently announced it will ditch its paper version), but that journalists and news companies are disappearing. There simply isn’t a business model – in the face of unpaid “competition” for news from Twitter, blogs and Google searches – to pay for the traditional media structure. There has a massive decline in newspaper revenue in recent years and it seems not a week goes by without some major publication announcing massive layoffs (128 staff, or one third of editorial, at El País, 46 layoffs at L’Équipe…). So a newspaper and website like the Guardian, though the fifth most-visited website in the world, still cannot turn a profit and has consistently operated at a loss of around £30-50 million over the past years, or negative £100,000 every day.

Of course, there are a few websites that beat the Guardian in terms of viewership and are actually profitable. One is the Huffington Post, whose business model revolves around publishing huge amounts of content by unpaid “reporters,” interns and bloggers. The other is the Daily Mail, which provides readers with a steady stream of cheap-to-publish and photo-laden celebrity gossip, wardrobe malfunctions, crypto-racist middle class scare stories, and “freak show” stories worthy of Rotten.com, featuring obesity, graphic health conditions and trauma…

There are some publications which are growing and even thriving today – such as The Economist and Bloomberg – which tend to be catered for business elites and financial investors. Others, such as again the Huffington Post and CNN boost their profits by blurring the line between independent news and paid-for advertising.

The Internet has made traditional media “inefficient” as they, through capitalism’s normal process of “creative destruction,” are gradually being purged from the economy. It is certain that computers and the Internet will lead to similar effects on other industries. Some sectors, such as television, music and film, look like obvious candidates for such “streamlining” in the face of YouTube and online piracy. In other sectors, the effect will be slower or even absent: Bureaucrats working for competition-free corporate oligopolies and government agencies will, though having less and less work to do, be able to keep their employment.

Globalization and the new “rootless” firm

In the media world, many firms continue to exist only by cutting corners, not paying people, catering to the economic elite or by simply publishing garbage. In many ways we’ve seen this kind of logic extended to corporations in general. Leading “Western” firms stay in business by:

1. Employing no Westerners (with the possible exception of a few underpaid and rightless services workers).

2. Not paying taxes.

Perhaps the most striking example of this is Apple Inc., which also happens to be the most valuable firm in the world today, its stocks and assets being worth over $550 billion. Apple today employs 43,000 people in the U.S. as well as 20,000 overseas employees and 700,000 overseas contractors. That is only about 6% of people that Apple employs are in the U.S. And even those employees, at least those below middle management, typically face low wages and weak job security. Compare this with the situation of General Motors in 1955, that year’s most valuable firm, which employed almost 500,000 people in the U.S. and only about 80,000 people overseas.

Contractors employed outside the U.S. have infamously bad conditions, notably workers of the iPad-producing Foxconn, which notoriously began addressing the issue of worker suicide by setting up nets around its factories…

In terms of taxes, it has been estimated that Apple paid $3.3 billion in taxes worldwide on profits of $34.2 billion last year, or less than 10%, through tricks such as opening a profit-processing office in Nevada which, unlike California, has a 0% corporate tax rate. This may in fact understate matters: In 2012, it was estimated that Apple paid less than 2% corporation tax on its considerable profits outside the U.S.

Mega-corporations in every sector from Exxon to Walmart are like Apple using armies of lawyers, accountants and lobbyists to maximize profits through tax havens and loopholes, employ underpaid staff in countries with weak labor rights, and, if they absolutely have to employ Westerners, provide the lowest paid and most “flexible” work possible. In some cases the lawyering technicalities really get pushed to the absurd, as when Apple successfully patented the iPad’s “rounded rectangle” shape.

It’s quite normal for corporations to do all they can to make the most money possible, that’s what they’re designed to do. But for the rest of us, in the age of globalization and the Internet, it’s a problem if you aspire to a decent working or middle class lifestyle.

It’s a simple fact: If you put underpaid, non-unionized, environmentally unsustainable Chinese (or Vietnamese or Turkish or Mexican…) companies and workers in direct competition with Western companies and workers, shackled by things like environmental standards and decent wages, the Westerners will simply lose. As a result, the big corporate giants and oligopolies that were providing ever more well-paying and secure working and middle class jobs in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, have been slowly going out of business or are no longer providing such jobs.

Western workers have, in some countries, reacted to this by voting for leaders who maintain worker protection, subsidize certain industries, ensure high wages for certain sectors, and the like. While partially effective at ensuring “good jobs” exist, this tends to raise the cost of work and thus result in higher unemployment for those outside the “system” (typically youth, minorities and seniors).

The alternative, notably instituted in the U.S., U.K. and Germany, is no more attractive: to maintain employment by pushing down wages and removing job security. So while in these countries employment tends to be somewhat higher than average, so are poverty and already unprecedentedly high levels of economic inequality. This trend is ineluctable and in fact was already identified by the Anglo-German scholar-politician Ralf Dahrendorf in a 1999 article entitled “It’s work, Jim – but not as we know it”:

“In all OECD [developed] countries, there has been a significant decline in the number of people in typical employment relationships: full-time permanent jobs (or, more precisely, full-time dependent employment without built-in time limits). The most thorough study of this change is that by a recent German commission. It concludes that ‘in countries where the employment rate has changed little, about a quarter to a third of typical employment relationships has been replaced by atypical ones since the 1970s’.”

What solutions?

The case of Apple shows as much as anything how bankrupt Western politicians’ strategies for promoting growth and jobs have been. The alpha and the omega remains “innovation,” beloved by both U.S. and EU leaders. But as the example of Apple shows, one can be the cutting edge technological firm and only marginally benefit your country. In what sense is Apple an “American” firm if 94% of its workforce is non-American and if it barely pays any taxes to the U.S. government?

Other Western strategies since the 1980s and 1990s – notably liberalization of financial markets, economic integration (such as the euro common currency) and ever more education – have shown their inability to ensure lasting growth and the maintenance of healthy middle classes. Often these actions are useless.

Young people (and governments) get into huge amounts of debt, and spend ever longer portions of their lives in a weird post-adolescent financial dependence, for the sake of education, that centerpiece of the liberal project. (Who can forget Tony Blair’s famous three priorities: “Education! Education! Education!”) Yet the usefulness of sitting around in classes in terms of social and economic progress is, after a certain point, highly doubtful. Germany, by any measure the most successful major developed economy today, has among the lowest proportions of university graduates at 29%, almost a full quarter less than the OECD average.

Often, as in the case of finance and the euro, the crisis has shown that liberal strategies of economic integration were actually destructive.

Are there any solutions to youth unemployment? Does the new generation of job-seekers really need to reconcile themselves to being worse off than their parents? There is advice one can give to individuals:

1. Join the privileged by finding employment with a good corporate or government bureaucracy (e.g. become a senior corporate manager or civil servant).

2. Find a personal niche of rich people (or corporations) to market your skills to.

3. If you’re blessed with unique genius and fortune, become the next Mark Zuckerberg.

Of course none of these can be real solutions for an entire country, as opposed to an individual. I personally still remember with an ironic smile some good advice we were given at a university career seminar: “Stand out from the crowd!” This was helpfully illustrated with a picture of a man walking on stilts above a crowd of people. Obviously, by definition, not everyone can stand out. It’s a purely selfish strategy to the problem of unemployment, it cannot solve the problem we face, but it’s the strategy that is often promoted by families (which is rational) and by leaders (which is irresponsible).

Collectively there are perhaps policies we could pursue that would maintain standards of living in developed countries. First, there needs to be effective coordination between countries to crack down on tax havens and ensure that corporate giants, the ultra-wealthy and financial firms pay a fair amount of taxes and reverse the trend towards ever more inequality since the 1980s. Second, we need to make sure that competitors abroad don’t have unfair advantages if their profits are based primarily on exploitative labor conditions and carbon emissions (i.e. if those countries don’t have comparable social and environmental standards).

Technological innovations and free trade after all do not in themselves impoverish, on the contrary, and the new “wealth” they do create can be put to good use if put towards public ends (we might, for example, change our tax codes and budgets to incentivize job-creation in areas such as urban renovation, energy efficiency or renewable energies). Indeed, globalization and new technologies have allowed new exchanges between countries, limitless access to information and unprecedented opportunities for aspiring artists and amateur journalists to share their work without corporate or public patronage. But our socio-economic models also need to adapt.

Actually putting international tax, environmental and social cooperation into practice is another thing altogether. For now, those unfortunate enough to enter the labor market today should not be afraid to ask for help from friends and family, should not waste money, avoid debt where possible, and keep looking. Perhaps most importantly, the social stigma and incomprehension at not finding a job, where it persists, needs to go away. For the individual, the psychological is typically as important, if not more so, than the material, because in addition to being poor and dependent, one needn’t make young people feel ashamed because of an economic crisis which, after all, their elders are ultimately responsible for. We shouldn’t forget that even in such a situation it is perfectly possible, in a stable and developed country in particular, to be happy, which is after all the point.

Tags: Apple, economic crisis, globalization, jobs, Media, unemployment, youth