Conscientious Technologies for a Sustainable World

This post was produced for the Global Economic Symposium 2013 to accompany a session on “Towards Sustainable Consumption.” Read more at blog.global-economic-symposium.org.

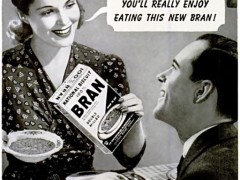

“It’s the greatest thing since sliced bread!”

I am from India, the country of rotis, parathas, and naans (among many other things). Sliced bread was never an important part of my diet. So, when I heard the phrase “the greatest thing since sliced bread” for the first time as a kid, I was confused. How did bread slicing become the gold standard of innovation and technological advancement?

Prehistoric inventions such as the plough and the wheel had universally altered the course of human evolution. The printing press redefined our thought culture. Then came the light bulb and automobiles, contemporaries of sliced bread. But none found their way into such a widely used idiom. So, what makes sliced bread so special?

First, it made food consumption simpler.

Food is intimately important to us. For the longest time in human history, food was difficult to come by. Our bodies evolved to live in a world of food scarcity. The invention of sliced bread arrived at a tipping point in our history: we now live in a world of food abundance, but our bodies are still geared for the old world. The technology of sliced bread (along with the technological innovations of refrigeration, corn syrup, mobility, and food processing) has altered the food landscape completely. It changed the conversation about food from one about nutrition to one about convenience.

Second, it was among the first symbols of mechanization in our daily lives.

Third, it was born out of an advertising slogan.

Advertising is the most efficient soldier in the service of globalized consumption. And good advertising creates strong cultural marks. The Chillicothe Baking Company, the pioneer of sliced bread, employed advertising and PR effectively. Born at a time when the concepts of technology and progress were fusing into one, the slogan made a lasting cultural impact.

The slogan is indicative of our obsession with convenience.

The shift towards more and more convenience, at the expense of almost everything else, has been the single biggest change in the way we live — all our technological endeavors are geared towards achieving more and more convenience. Technological innovations are working overtime to make our already sedentary lives free of any small effort needed to consume something. Technology has created this sense of entitlement to convenience at any cost. It is taken as common sense that new products should be created to make particular acts easier, even if the social, economic, or ecological cost is prohibitive (water in plastic bottles, processed foods and the consequent food deserts and food swamps, to name a few examples).

With the advent of the information age, the search for convenience extends to newer and newer created needs. Take, for instance, the latest innovation from Google: Google Glasses. The news of the launch also launched a wave of anxiety — the fear of privacy infringement, of further erosion in social interactions, and so on. This brings into focus a question that begs to be asked.

The starting point for technological endeavors should not be “what can technology do?” Because, it is with questions like these that artificial needs are created. (Create a product first. Then convince people they need it.)

Perhaps, the starting point should be “what do we really need right now, and how can technology help us get it?”

Which brings me to the question of genetically modified foods. We need sustainable sources of food, and some people believe that GM crops will prove to be the answer. But experience has shown that GM crops pose more uncertain risks than certain gains. GM crops are threatening to irrevocably alter our ecology in favor of big corporations like Monsanto by snatching away a basic freedom from small farmers: the freedom to harvest the seeds of their own crops. The ill-devised copyrighted technology of corporations like Monsanto is trying to control the life source of food and is threatening both our ecology and our rights with profit motive. Rather, it is the non-copyrighted technologies of organic farming, traditional practices, and agroecology that hold the key to sustainable food production — which benefits not just the consumer but the farmer, too. Because these technologies do not lend control to a corporation, however, they do not receive as much financial support.

Companies are eager to “lead the change” and “make a dent in the universe,” but to what effect and at what cost? Maybe it is time for a new approach to technology — an approach that is aimed at solving a real need, through humane means. We need a more humanist and realist take on technology. We don’t need utopias or grand narratives of progress; we need simple steps that empower and enable well-being.

Marshall McLuhan argues that technologies are not simply inventions people employ but are the means by which people are reinvented. It is time we ask ourselves what we want to be.