Have we reached the limits to growth? Where you sit is where you stand!

“Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever, is either a madman or an economist.” (Kenneth Bouldin, economist)

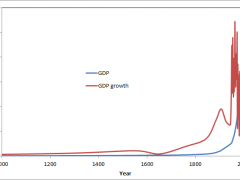

At university, the first graph we were shown in the economics class was plotting GDP growth in time, throughout the history of humanity. It turns out growth is actually a relatively novel economic phenomenon (less than 200 years old) and that several centuries did not have any growth at all. I remember being shocked at this graph – as a young person who grew up in Eastern Europe, where we had experienced steady growth from the fall of the Iron Curtain to when the crisis first kicked in, I had taken for granted the idea that growth is indefinite.

After all, neoclassical economic models (like the Solow model or the Cobb-Douglas production function) told us that economic growth is a bidirectional function comprising two factors of production – capital and labour. Only more recently, advanced statistical modeling has shown that the classical combo (labour and capital) explains only 15% of economic growth and that a tridimensional function, comprising capital, labour and useful energy, offers a more comprehensive, more plausible explanation. Cheap energy, figures demonstrate, has been one of the major driving forces behind growth.

With the number of available cheap energy sources becoming less and less reliable, you naturally wonder about the limits to growth. One of the first proponents of the “limits to growth theory” is the economist Herman Daly who coined the model of the steady state economy. Daly introduces his theory by saying;

The closer the economy approaches the scale of the whole Earth, the more it will have to conform to the physical behaviour mode of the Earth. That behaviour is a steady state – a system that permits qualitative development, but not aggregate quantitative growth.

He argues that in high consumption countries expanding the economy quantitatively increases environmental and social costs faster than production benefits. Indeed, several countries of the Western world are already experiencing growth rates close to zero and low inflation, while the population is reasonably well educated, healthy and fulfilled. Have they achieved a steady state economy, and thus an end to growth as we know it? Most probably yes.

Daly puts forward a bunch of empirical evidence which proves that in developed, high consumption countries growth is already uneconomic. Increases in GDP still increase welfare in poor countries, provided that growth is reasonably distributed (for this reason, the rise in inequality in the BRICS and emerging economies in general is profoundly worrying in my opinion). Moving forward, the definition Daly and similar schools of thought give to a steady state economy is credible:

A SSE is an economy with constant population and constant stock of capital, maintained by a low rate of throughput that is within the regenerative and assimilative capacities of the ecosystem. This means low birth equal to low death rates, and low production equal to low depreciation rates.

However, the policy actions prescribed by such thinkers sound quite surreal, at least for Eastern European ears, who’ve embraced market capitalism as the Holy Graal, after years of stagnation, repression and poverty during socialism. They include such things as a minimum and a maximum income, the creation of citizen endowments, a massive increase in inheritance taxes, a redistribution of ownership, etc.

Removed from the circles of radical economic thinking and way more prudent, even the European Commission is suggesting ways to measure progress beyond GDP. In the wake of the “Beyond GDP: EU Roadmap 2009”, it proposed a set of five key actions, which are worth monitoring: complementing GDP with highly aggregated environmental and social indicators; near real-time information for decision-making; more accurate reporting on distribution and inequalities; developing a European Sustainable Development Scoreboad; extending National Accounts to environmental and social issues.

Overall, some pieces of the SSE model sound quite applicable to developed countries (Western Europe, North America). On the other hand, accumulations of inequality and redistribution issues are plaguing many parts of the world, especially emerging economies – the Chinas, Indias and Brazils of this world. As far as Eastern Europe and my home country Romania are concerned, the puzzle of growth, sustainability and distribution must be looked at from the perspective of the European Union. Yes indeed, we must manage our natural and human resources carefully. Yet even so, we live on average shorter lives than our EU peers in Western Europe, we still have 30% of the population living on under 5 dollars a day and our average wage is six times lower than in Western Europe. We must still catch up and expand prosperity. From an Eastern European perspective, the limits to growth haven’t been reached yet. From a Western European perspective, things might be different.

Tags: beyond GDP, Eastern Europe, economic growth, gdp, Herman Daly, indicators, inequality, limits to growth, measuring progress, New Economy, redistribution, romania, steady state economy, sustainability, western europe