Cambodia’s Labor Market at the Crossroads

This article was originally drafted by Indochina Research for the newsletter “I-Light” as part of the Rockefeller Foundation’s Searchlight Process. For more Searchlight content on futurechallenges.org, please click here.

At present, Cambodia is enjoying an investment-driven boom, with the economy growing at 6.5 per cent, according to The Asian Development Bank’s growth projection for this financial year. According to World Bank estimations, however, the Kingdom’s economic growth is only able to generate about 30,000 new jobs each year, while the number of young people entering the work force has ballooned to about 300,000 per annum.

Workers in Phnom Penh. (Photo by Iefetell from flickr.com CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Unfortunately, Cambodia also stands out for its low-skilled labor force compared with its neighbors. Sixty-three percent of Cambodian youth either have never attended school or quit before completing basic secondary education. A full ninety-four percent of the youth labor force has not completed secondary education – a major obstacle to ensuring gainful and productive work. “Despite rises in productivity, the overall output level per work remains low in comparison with other ASEAN countries. Raising productivity levels within Cambodia is vital if the country is to remain competitive in relation to its ASEAN neighbors,” according to the International Labor Organization. “

In order for the country to escape the low-skill/low-wage trap, there needs to be an escape route. Increased skill acquisition allows for progressively increasing productivity that allows for increased wages and purchasing power – a virtuous circle. The alternative is not only the potential for social unrest but the threat that industries based on the nexus of low skills and wages will suddenly decamp to greener pastures.

Recently, in recognition that the system desperately needs to be upgraded, the Asian Development Bank undertook an in-depth analysis of the current status of Cambodia’s Technical and Vocational Educational Training (TVET) system. One of the key findings of this review was that currently there is a huge mismatch between skills supply and what industry is looking for. Foreign languages, IT, sewing, plumbing, carpentry and blacksmithing are all skills that are in high demand but where it is difficult to find workers with the requisite training. In the hospitality sector, employers identify difficulties finding chefs, receptionists and food and beverage managers. In the garment sector, a mainstay of Cambodia’s fledgling economy, positions that stand out as the most difficult to fill are in sales and sewing. In the construction sector, it is hard to recruit carpenters, plumbers, blacksmiths and electricians.

A country with a poorly trained labor force will face problems attracting foreign direct investment to upgrade its production technologies to stay ahead of the game. It then risks remaining trapped in a vicious cycle of low productivity and anemic growth. The major challenge now is to provide relevant education and especially training for new workers, to avoid poor skills becoming an impediment to the growth of the country in the future.

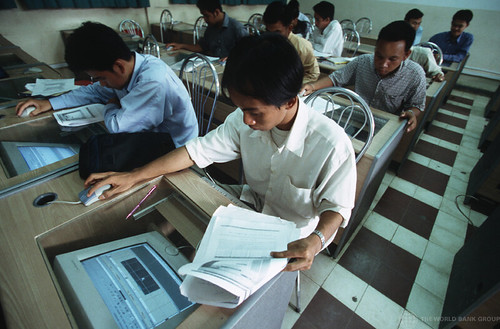

Students take a computer course at a private school in Phnom Penh. (Photo by World Bank Photo Collection from flickr.com CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A startling anomaly in Cambodia is that seven out of ten university graduates (usually in business and economics) are currently surplus to requirements – the only significant pool of unemployed youth in the country – according to The Economic Institute of Cambodia.

73 percent of employers reported that university graduates do not have the right skills, while 62 percent of employers had the same complaint about vocational training graduates, according to a survey carried out for the World Bank in 2011 and published this year in the technical paper, “Matching Aspirations: Skills for Implementing Cambodia’s Growth Strategy”, In fact, management jobs in Cambodian factories have been dominated by foreigners who have both the requisite skills and experience, as well as the language skills to communicate with owners and investors, who usually speak English or Chinese.

However, training Cambodians to fill these jobs would confer considerable advantages. They would speak Khmer and so could more readily communicate with their line workers. They also have a profound understanding of the culture – a source of frequent problems with workers on the shop floor. Finally, they would be expected to command much lower pay scales than for imported labor.

There is an opportunity here for the private sector and nongovernment organizations to step up to the plate. While it is true that somewhere between 28 and 50 NGOs providing valuable informal training, mostly to disadvantaged youth, especially in soft skills which greatly enhance the durability of employment, this only addresses the most pressing needs at the bottom of the pyramid. Currently there is no mechanism for helping kids from poor but functional families finance vocational training – a major constraint on access – through, for instance, micro loans (ideally guaranteed by future employers – who would ultimately benefit from a higher skilled workforce). Such a mechanism would also support teaching institutes, such as technical schools, as well as the various for-profit providers, by creating sustainable sources of revenue for them – a major constraint on their development at present. Such capacity building would help to address a current market failure, as well as reduce the country’s dependence on foreigners filling these key niches that risks condemning locals to the least valuable jobs in the local economy.