The Tipping Point

In 2008, our world crossed a demographic Rubicon: for the first time in history, more people lived in urban areas than in rural ones. On a planet effectively bursting at the seams, where megacities are growing faster than ever before, the question of whether the built environment is sustainable is a pressing one indeed.

American sociologist and historian Lewis Mumford contends that for a city to operate effectively, certain constraints ought to be applied on the population, modern development, and density. However, considering the unprecedented acceleration of urban growth, Mumford’s suggestion seems a little idealistic. Not only are the physical forms of urban areas continually being reshaped by their perpetual expansion, but the living conditions of many of their inhabitants are also altered as we attempt to evolve in unison with these rapid changes.

In recent years, China has seen a particularly significant shift of its population, from traditional rural areas and the legacy of rice farming to urban areas and a focus on factory work. Today, 51.3% of China’s 1.35 billion people live in urban areas. Just three decades ago the number of city dwellers comprised only one fifth of the country’s population.

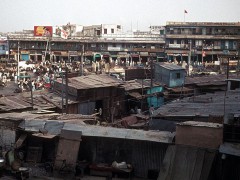

What may prove problematic with mass migration from rural to urban environments is not growth itself, but unplanned growth. The United Nations Population Fund estimates that a little over 31% of the world’s populace – around one billion people – are currently living in slums and impoverished circumstances. In India’s capital, Delhi, the drastic contrast of urban growth and urban impoverishment has become a serious issue. A recent survey has shown that a third of the world’s malnourished children live in India and, more specifically, in India’s urban slums. The idea that the city can offer better living conditions and healthcare only holds true for a privileged minority.

Disillusionment of the city and its destructive effects has caused city-dwellers around the world to view rural life through an idealistic lens. Interestingly, in our very own South Africa, a similar kind of rural/urban dichotomy was, once upon a time, actively encouraged by the apartheid government to discourage black urbanization of South African cities. The city was portrayed as dirty, corrupt and dangerous; the rural homesteads were pure, moral, idyllic, and unspoilt.

Conversely, there is no denying the devastating and direct impact that urbanization has on the natural environment beyond the city. This is realized in part through the emission of greenhouse gases in cities leading to global warming and climate change beyond their borders (think crops and agriculture being spoilt by unprecedented levels of rain or, conversely, by droughts). Beyond this, more and more rural spaces, as well as animals’ (and sometimes humans’) natural habitats, are rapidly and literally being trodden down or chewed up by this ever-expanding cow of urbanization.

We should wonder, then, if there is any realistic solution to minimise these consequences, especially when living ‘green’ in our current society is largely a luxury, one that only the elite tend to be able to afford.

A recent buzzword has been ‘hedonistic sustainability’, an idealistic yet potentially useful architectural concept developed by Danish super-architect Bjarke Ingels. His latest proposal for 2012 is an urban waste-processing power plant in Copenhagen transformed into a multi-purpose urban ski slope. The plant simultaneously produces heat and electricity for 140,000 residences while skiers take chair lifts up and then ski down the slope.

Although at face value Ingel’s project typifies a green idealism often reserved for the urban elites of first world nations, its greater value lies in the potential to fuel and yet feed off this urban elite’s desire for ever-improving quality of living at once, creating sustainable energy and development in the process.

For the time being though, at least within much of the developing world, it seems that megacities will continue their meteoric growth, often producing devastating symptoms. But surely there’s no ailment a little skiing can’t cure!

Amber Kriel and Christopher Clark are members of Global21, a student-run network of international affairs magazines and a partner of FutureChallenges.

Tags: Cities, Development, ENVIRONMENT, global civil society, globalization, india, sustainability, urbanization