Wheels against wheels: bicycles in Quito

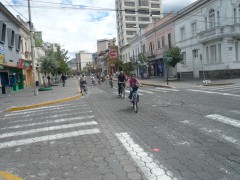

A view of Avenida Amazonas on Sunday, July 15th, 2007. To this day the place hasn’t changed: every Sunday bikes take the road in Quito, Ecuador. Photo by Helder Ribeiro, on Flickr.com, CC BY-SA 2.0

Salomé Reyes was an elite cyclist. She was also a dentist. She participated in mountain bike and urban competitions and was well known inside the Quito sports circuit. In late April she was training for a cycling tour around Ecuador with several friends on the bike path in Cumbayá, a rural parish to the east of Quito. When they finished training, she rode along the highway to return to her car which she had left in the parking lot of a mall. Suddenly a bus hit her. The driver failed to see her and didn’t stop. After knocking her down, the bus ran over her. She died instantly.

Salomé was 33. The bus driver fled.

Sometimes in Quito the interaction between road users —cyclists, drivers and pedestrians— is like Jurassic Park: humans versus huge wild creatures. Other times it’s like the chariots scene from Ben-Hur. In very few cases are users aware that other users are also people. It doesn’t matter if they’re in a car, on bicycles or on foot. A battle is being waged in the city.

And it’s a painful confrontation. In April this year alone, seven cyclists were run over in Quito (and these are only the official figures). And in an absurd turn of events, a cyclist was almost hit by a vehicle during a protest following Salomé’s death in the area of Avenida Los Shyris. Sadly, the logic of the local roads is absurdity writ large.

“The streets of Quito are quite violent. If you use any kind of public or private transport, walk or ride a bike, you’ll always find that the strongest or the craziest want to get their way, but nobody does the basics which means enforcing traffic rules”, says Luis Eloy Salazar, a city resident who enjoys riding his bike on Sunday’s Ciclopaseo, in Quito. The Ciclopaseo started in 2002 as a private initiative (currently the Ciclópolis Foundation is responsible for the organization). Nowadays it has the support of local authorities and allows cyclists to ride 29 km across the city from north to south every Sunday. During the Ciclopaseo, Quito seems to have another color, another sound and another way of living. No cars are allowed on the Ciclopaseo’s lanes, only bicycles until 2 pm, when it all ends and the lanes are once again taken over by vehicles.

A project such as the Ciclopaseo is a natural and necessary response to a city like Quito. A city that lives in chaos because to go from point A to point B drivers are stuck in traffic for hours, given the incredible amount of vehicles on the streets. frustrated drivers don’t see beyond their own cars. Their hands are glued to their claxons in attempts to speed up the drivers ahead. They don’t respect pedestrian crossing lines because they don’t care about them. If the traffic light turns yellow, they are more likely to accelerate than slow down.

Nearly 450,000 vehicles are packed into the city’s streets every day. The fact that Quito is just 50 km long and only 4 km wide only makes matters worse. There is simply not enough room for so many cars. And, of course, there is not much room either for the people who are not motorized. In 2011, there were 22,266 traffic accidents in Ecuador. Of these, 69% happened in the cities. While Ecuador has taken drastic measures to make drivers respect the speed limits to avoid accidents (including imprisonment for those who violate them), violence is still up front. Even though accidents have been reduced by almost 50%, much work still needs to be done.

Norman Wray, a Quito city councillor, puts it in perspective in a post on his personal blog: “In Quito, the leading cause of violent deaths are traffic accidents, even more than fights, assaults and theft.”

The truth is that cyclists are being injured and sometimes they hurt other road users too. There are sections of the Ciclopaseo in which pedestrians can not cross the streets because of the huge number of cyclists who choose not to stop at the red lights because no cars are in view. This happens, for example, in Avenida Amazonas (in the north of the city). Some cyclists also strongly criticize the new municipal legislation that prevents bicycles from riding on the sidewalks.

“Pedestrians and motorists lack something basic: any consideration that bikes are also vehicles. I have seen the traffic education campaigns but all of them are focused on pedestrian-motorist interaction. They should also include cyclists and users of public transportation as well,” says Luis Eloy.

If a peaceful consensus in this matter is to be reached, people should respect and recognize others. The public bicycle project recently launched by the municipality is one interesting option. Since last August you can see people using public bicyles to go from their homes to their places of work or study. The project has given the city 425 bikes which can be taken by citizens in 21 points around Quito. Everyone can register and use this service for $ 25 a year. Sure, there is a fixed maximum cycling time of one hour after which users must return the bike to a point.

What we now have is cyclists using roads with more freedom and a growing awareness that private and public vehicles are not the only means of transport that can be used in Quito. There really are more options. People are now happy that they’re not arriving late anymore because of traffic jams. Using bikes on a daily basis does save them precious time.

At the end of the day, peaceful coexistence is just a matter of having good ideas.