Good Jobs vs. Any Jobs: Do we have to choose?

In countries hardest hit by the global financial crisis, unemployment for young professionals can reach nearly 50%, far superior to unemployment rates among the active population over 25. For those lucky enough to find jobs, they are often precarious short-term contracts that offer little hope of future stability, even for the best educated.

“Génération CDD“; The French have given a name to an entire generation of young graduates that is struggling to find secure employment, even after five or more years of higher education. This name refers to a certain type of employment contract, a ‘limited duration contract’, that many young professionals find themselves reluctantly accepting.

These contracts are much cheaper for companies and offer the important advantage of being much more flexible as employees can easily be terminated at the end of their contract. Under French labor law, it can be very difficult and, subsequently, quite expensive, to lay off workers with a prized CDI, or, “unlimited duration contract.” The CDD and the similar “intérim” (temping) contract are an understandably important means for companies to continue to operate during uncertain times. However, they have a serious implications for young people trying to begin their professional life.

Many young people find themselves renewing CDD contracts year after year in the hopes of one day being offered a permanent position, with the security that entails. Currently, three-quarters of the jobs being created in France are flexible limited duration contracts. The CDD not only leaves employees wondering if their contract will be renewed at the end of the year, but it also makes it much more difficult to begin to construct a life, with banks and landlords hesitant to lend or rent to workers without the assurance of a permanent position. Furthermore, years of short-term employment, often in radically different positions, is frowned upon by employers, making it difficult to build up a CV.

Many young people thus find themselves in a sort of vicious circle, accepting whatever temporary contract they can year after year, unable to invest in a home or build up crucial professional experience that will allow them to reach the Holy Grail, a CDI.

These problems transcend the recent global economic turmoil, however, this “système à double vitesse” or “two-speed system,” further exacerbates the difficulties for a segment of the population that is typically one of the hardest hit by economic slowdowns.

Structurally screwed

It is no new phenomenon that young people are among the hardest hit during economic slowdowns. Typically, job cuts will disproportionately hit the least senior workers in a company and, further reinforcing this tendency, in the overprotected job markets that are common to Europe, young people are often hired by means of precarious temporary job contracts, such as the CDD in France, that do not afford the same levels of protection as more senior employees. Thus, one of the major “competitive advantages” of young employees, their relatively low cost, is offset by the costliness of shedding more experienced and well protected staff.

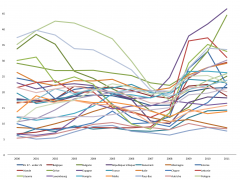

For the new positions that are created by companies during economic slowdowns, much more emphasis is placed on experiences, thus directly affecting young people right out of school with little work experience. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the often dramatic difference between unemployment numbers for younger and older workers.

Figure 1: Harmonized annual EU 27 unemployment, under 25

Figure 2: Harmonized annual EU 27 unemployment, 25 – 74

Source: Eurostat

Thus, while national education systems and economies have struggled to adapt to the demands of a changing, ever more competitive world economy, leaving young graduates more precarious than ever, rigid labor markets that pit a precarious younger generation against an aging cohort of overly protected workers can account for much of the woes of Europe’s youth. Yet, the adjective “rigid” is often applied in broad strokes and conflates hard-won social advances with ill-conceived labor market policies that have deleterious effects on employment.

Common wisdom for liberal economists holds that European labor markets tend to be rigid, with high structural unemployment, while American labor markets are more flexible and dynamic, resulting in a much lower “natural” unemployment rate. This “old refrain” obfuscates the diversity that exists in Europe between different countries and certain anomalies immediately call into question the validity of this supposed truism. For instance, see figures 3 and 4 below.

Certain elements of what economists call labor market “rigidity” may not have as much of an effect on structural unemployment as imagined. Basic norms such as strict employment practice standards that protect workers from arbitrary, unfair or discriminatory practices do not heave a substantial negative impact on employment numbers. Equally, most minimum wage legislation is low enough to not have any substantial effects on the labor market. Finally, unionization in an of itself is not strongly correlated with high structural unemployment.

Figure 3: OECD “employment protection” index and unemployment

Source: Eurostat/OECD

Figure 4: OECD ’employment protection’ index and employment rate differential

Source: Eurostat/OECD

Nevertheless, certain aspects of European labor markets significantly raise the level of natural unemployment and concentrate the effects of economic slowdowns on young workers.

Labor supply measures, such as early retirement or mandatory maximum working hours tend to not be effective. Generous unemployment benefits that can continue indefinitely as well as high payroll taxes are both correlated with high structural unemployment. While the level of unionization does not automatically imply higher unemployment, the widespread practice of collective bargaining for wages does have a negative impact. Finally, hierarchical labor contracts, with a core of highly protected workers and various precarious instruments for limited duration employment are strongly correlated with high unemployment, especially for youth.

Figure 5 paints a striking picture of the correlation between “employment protection” and the gap in unemployment numbers between younger and older workers. Of course, such a simple diagram can only portend to illustrate a very general correlation and not any sort of rigorously tested causality. It ignores many of the complexities of this situation that such general indicators cannot represent. Additionally, there are some outliers, such as Greece, Spain, Germany and the United Kingdom that call into question the validity of this interpretation, although the variable impact of the economic crisis can account for some of the deviance.

Figure 5: OECD ’employment protection’ index and unemployment differential

Source: Eurostat/OECD

While the idea of labor market “rigidity” tends to bundle a number of measures together, in reality, the effects of these policies are much more diverse. Policies such as strict norms the protect workers from arbitrary dismissal are basic rights that, additionally, do not have very much effect on unemployment. However, other characteristics such as high payroll taxes and two-tier employment contracts are very highly correlated with greater unemployment.

Tags: employment protection, France, jobs, unemployment, youth, youth unemployment