In Hungary we don’t use the A-word

Politicians, economists and other experts speak gravely about the need for austerity measures on a European and global level. But when it comes to governing their own country, leaders try to avoid using the A-word. Even if they actually do implement some kind of cuts in government spending, they all have to be packaged in clever rhetoric.

Obviously austerity is a term that doesn’t sell well. Nobody likes to hear about their wages being cut. And when this unavoidably happens, a culprit must be found, someone at whom you can point the finger of blame. This is a very important detail: who is responsible for the cuts in my income? Or, more accurately, who do I – an average citizen – think is responsible for the cuts in my income?

Is it the government of my country? Well then, they won’t get my cross at the next elections! This is a point Dániel Vékony made well in his recent article on austerity: “…any government brave enough to introduce […] reforms would also risk not being re-elected for another term. […] the very logic of our democratic systems prevents politicians from carrying out those very measures that guarantee our long-term economic competitiveness.”

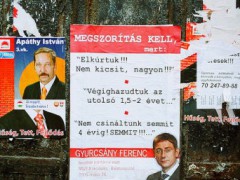

“Austerity is needed, because… we haven’t done anything for 4 years!” – famous words by the then Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány during a party meeting behind closed doors. Photo by habeebee on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Scapegoating is one classic pitch for selling the message about cuts. In this case, it is permitted to say the A-word out loud, because it isn’t the government which is forcing citizens to suffer. Who is it then? Possible candidates can be the EU or some EU member states (see the post by Rani Nguyen on Germany’s role in this context), or indeed the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Hungary received an IMF credit in 2008 (to help it cope with the crisis) which was granted on condition that the country made severe cuts in public spending.

The minister of economics at that time was Gordon Bajnai who later became prime minister of Hungary (2009-2010). During his one year as the “crisis manager” prime minister, whenever he had to implement austerity measures, he would point in extenuation either to the IMF conditions or to the overall situation – i.e. that we were trying desperately to avoid a complete melt-down. His strategy of justification seems to be working now and his chances of becoming prime minister once more will be tested in the 2014 elections.

What has been happening in Hungary since 2010 might be even more interesting when viewed in terms of the skillful use of rhetoric. Very often the word “austerity” is replaced with “reform”. This sleight of hand has been used so often that the word “reform” now has the same deadening effect on people as austerity. In its original meaning, reform should bring something new and better – but Hungarians really don’t buy that any more.

The Orbán government has evolved a much more sophisticated set of expressions to present its policies than simply substituting austerity with reform. The term “unorthodox economic policy” has been invoked to describe the various and often surprising measures implemented by György Matolcsy in his function as minister of economics, and to explain why these measures are sometimes the reverse of what the European Union suggests. After all, we do it our way.

This time around not only select terms but a whole reference framework has been evolved. Take, for instance, the expression “fight for economic freedom” (which refers to Hungary’s fight for political freedom in 1956, I suppose) or even “System of National Cooperation“ [HU], which, according to the government, stems from the new social contract, born as a result of the 2010 elections where Fidesz won two thirds of the vote.

Yet there is another, very different way to handle the austerity problem. Legends speak of countries where well-informed citizens understand their responsibilities and in the name of solidarity pay up, and accept cuts in spending if necessary. But present-day Eastern Europe is not the stuff of which such legends are spun. After all, in CEE citizens don’t trust their governments, and are not willing to fork out money for governments widely perceived as corrupt (which indeed they often are). Generations of voters have been trained in this way of thinking, and such a deep-seated attitude will take an extremely long time to change – if it ever does.

Tags: austerity, Central and Eastern Europe, Hungary, reform, rhetoric