An Open Question: Bhutan’s Maturing Democratic Culture

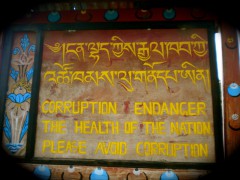

A signboard warning Bhutanese about the health hazards of corruption. Author: Manny Fassihi (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0)

In 2008, Bhutan completed one of the most peaceful – and ironic – transitions to democracy. Initiated by the Fourth King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the process involved a voluntary abdication of power in the face of public opposition to democracy.

Imagine the living embodiment of a Platonic Philosopher King, someone universally loved for his enlightened leadership, relinquishing power to a system that has fared tenuously, at best, throughout the region.

And yet, the Bhutanese are aware that there is no turning back.

At least, His Majesty the Fifth King, who retains symbolic authority as Constitutional Head of State, won’t allow them to. All along the way, he has been supportive of the transition, vesting his legitimacy as King on the success of the democratic system.

While many hallmark democratic institutions have been set up – a model constitution, an independent judiciary, legislative, executive and media – democratic culture has still been slow to emerge. The challenge for the Bhutanese is a challenge of psychological reorientation, as they shift their status from being subjects to being citizens.

Many people don’t feel any need to change. Indeed, life before democracy was much simpler for the average Bhutanese, as Nitasha Kaul writes:

Under the King, the state provided extensive support for the population. Education and healthcare were free. Educated people could get any kind of comfortable, permanent jobs they wanted in the civil service. It was common for the landless to be granted land under the kidu (“welfare”) system. If you were a farmer, as over 70% of the population were, you could confidently rely on the strength of your community to solve any problem.

People are also reluctant to embrace the “culture of criticism” that characterizes most democracies. Bhutanese culture places a strong emphasis on social harmony and the avoidance of conflict at any cost. This is typical in most interactions, where any suggestion put forward, and especially those put forward by leaders, will be met with a “Lasso La” (which roughly translates as “Whatever you say, sir/madam”).

Ideally, a person is expected to work for the good of the group and to adjust themselves according to other people’s expectations. Rarely do people choose to disagree openly. In a small society where “everyone knows everyone”, disagreement risks your losing face and becoming the butt of gossip – and the culture of gossip is quite strong here!

By no means do I intend to suggest that all of these norms and artefacts are anathema to democracy. However, as some commentators (and even high Buddhist Lamas) have pointed out, these traditions should be critically reviewed and not merely held on to for the sake of tradition.

And, of course, culture does not change overnight.

Nevertheless, times they are a changin’ – and changing fast. For one thing, people’s consciousness of their rights is rising. The Bhutanese are beginning to question the government’s authority to enact policies made for the “public good”.

Take, for example, the recent “Pedestrian Day” , a unilateral decision made by the Executive Cabinet intended to limit car usage on Tuesdays. Many endorsed the spirit of the law – walk more, develop healthy habits, and save on gas expenses. However, the policy brought with it many unforeseen negative consequences, particularly delays and loss of productivity in the private sector. People are now voicing their disapproval of the government, and even accusing leaders of international exhibitionism.

To the government’s credit, they are indeed encouraging feedback and making no attempts to forcibly censor people.

The media is also creating the public space for the people’s voice to be heard. With 2 TV channels, 6 radio stations, and 12 newspapers people have more access than ever before to news, views, and opinions. Concurrent with this growth has been an emboldening of the media to ask questions. It’s not uncommon now to see front-page stories on corruption scandals, failures in government policy, and even cartoons mocking high officials.

Unfortunately, the media, which in the main is composed of untrained journalists, has begun to follow some of the more doubtful global trends, reporting predominantly negative stories and developing an adversarial relationship with the government. Cynics now abound, and some of them have even gone so far as to proclaim the death of Bhutan’s democracy after a controversial advertisement circular.

There are still many open questions ahead: how can underprivileged populations, like youth, be more included in decision-making processes? How can Bhutan attain economic self-sufficiency and independence when the agricultural sector – the basis of Bhutan’s economy – is rapidly shrinking due to rural-urban migration? How can people be motivated to shoulder all the responsibilities that citizenship entails?

Bhutan is a country of great aspirations, none less so than “Gross National Happiness”, its drive to find a middle way to development. While these aspirations have yet to be fully realized, what’s reassuring is that the Bhutanese people continue to voice the questions. While most democracies have already made up their minds, Bhutan is at a momentous period in its history when it can dare to dream up something different.

Yet another signboard reminding citizens of their fundamental duties. Will the people take heed? Author: Manny Fassihi (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0)