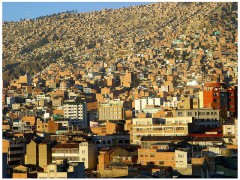

Bolivia’s economic growth seen from a different angle

The article responds to the Secrets of Transformation multimedia series, a joint project of Bertelsmann Transformation Index and Deutsche Welle.

Transformational is without a doubt the best word to define the past decade in Bolivia. Changes began even before Evo Morales became the country’s (and South America’s) first indigenous president, as people campaigned for changes to the government’s policy on natural resource management and for more participation by the indigenous majority in state affairs. Both these demands—and others such as the reestablishment of the Bolivian state and the rewriting of the Constitution—have been finally achieved by the Morales government after decades, if not centuries, of struggle.

This is why since 2006, political transformation has been daily bread for us Bolivians. But, what impact has such transformation had on our daily lives? The fact is that our political transformation over the past few years has been so dramatic that it’s difficult to see the changes that are taking place in the economy, healthcare, or education. And we don´t really know if all this transformation is just an excuse for the lack of new policies in these areas. The truth is that we can´t really tell unless we have access to data collected by international organizations that point towards actual growth and improvement in Bolivia.

During the first months of the Morales government, everyone was paranoid about what the new government might do to private property, private enterprise, and foreign investors. The ruling party wanted private property to be redistributed among the poorer population to drive social transformation. Both Bolivian and foreign private investors have definitely felt the squeeze of strong state involvement in the economy. Even so, private property has been left untouched, which eventually has led to a slackening off of the paranoia felt by the great landowners and their ilk.

The greatest economic change we have perceived is stability. We are all aware that our economy depends on the international commodity prices of minerals, metals (tin), and grain, and the high revenues from the nationalized gas industry’s exports to Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. However, that´s not all: The banks are doing very well and private bank reserves have more than doubled, which is a great comfort to the private sector. Ironically, this is in large part due to Bolivia’s limited participation in international global markets, which has kept the country’s economy relatively safe from the shocks of the international crisis. This result is fiscal surpluses that translate into bonuses and constant salary increases for workers in healthcare and education.

However, what we are still not seeing is what social movements of miners, workers, agrarian workers, and so on are constantly calling for—namely, a more drastic redistribution of wealth. Morales´s present plan of economic redistribution is mainly based on bonuses for various vulnerable sectors of society, such as mothers and their newborns, school children up to the age of 12, and people over 60. But anyone who doesn’t fit into one of the above categories suffers under constant price increases, a lack of legal security for private enterprise, and a lack of favorable commercial agreements. This means that Bolivians both urban (entrepreneurs, freelance research workers, constructors, lawyers, and the vast informal workforce) and rural(small agricultural enterprises and workers and their families) are having a difficult time taking part in the economic growth the country is experiencing.

So not everybody is happy with economic growth because not everyone is actually getting a cut of it, or finding new opportunities to do so. And it is the persistence of such dramatic inequality that gives Bolivia one of the lowest ratings in the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) for its performance over the past years. We can read that there are considerable improvements, but the road ahead to our so ardently desired social transformation is still long and arduous. The road is easier when there is a strong economy, of course, but what Bolivia urgently needs is a deep and constant social transformation, especially for women and children. Just to point a couple of the demanded changes we are still awaiting for: we would like to see tighter employment policies and investment (no more bonuses) in health and education that can actually make a difference in the future. These are definitely better days, we know it and are grateful for it, but we cannot afford to sit back on our laurels because there is still much to do and much to fight for.

Tags: bolivia, BTI, BTI: Economic growth, Development, economic growth, Evo Morales, pro-poor growth