Catcalls and the right to the city

JULIANA CUNHA

In Brazil, a campaign against catcalls is drawing attention to the situation of women in cities.

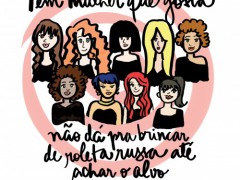

“There are women who like it”

You cannot play Russian roulette trying to find your target. Illustration by Gabriela Shigihara. Courtesy from the artist.

Male catcallers are found in many places around the world and there’s no shortage of them either in any city in Brazil. It’s highly unlikely for a woman to spend a day alone in a city like Rio de Janeiro, Salvador or São Paulo without being catcalled at least once by some strange man who decides to stop whatever he’s doing to say exactly what he thinks of her body or give details about all the stuff he’d like to do with it. The fact that this body is actually hers is somehow an inconvenient detail.

In Brazil, many people, both men and women, think that catcalls are a compliment, a form of positive interaction that breaks the cold hard surface of urban life, a dash of friendship, a human element that is often associated with (and praised by) Latin American peoples. Journalists Juliana Kenski and Karin Hueck couldn’t agree less with such assertions. In August 2013, they launched an online survey with 7,762 participants that indicates that 99.6% of Brazilian women have been harassed in public places. 83% of respondents said they did not like being the butt of such compliments in the street. The survey is part of Kenski’s online campaign to denaturalize catcalls.

The survey is creating a buzz in both press and social networks in Brazil. On one side there are those who advocate preservation of this habit seen as a typical Brazilian cultural trait. On the other side, there are people who believe that catcalls are just a veiled way of curtailing women’s participation in public life that limits their right to walk around the city. “Women have their right to come and go restricted. Many of us have to chose longer paths not to pass by a bar or cross a group of men. Many girls give up wearing what they want and go for clothes they believe will not draw so much attention from men”, says Kenski in a interview for Future Challenges.

According to Alessandro Janoni, research director at Datafolha — one of the largest polling institutes in Brazil — the poll proposed by the campaign presents a number of methodological flaws and cannot be taken seriously. “Perhaps the intention of the campaign was not establishing the percentage of Brazilian women who have suffered harassment on the streets or what they think of this kind of approach, but since the research got so much publicity and its intentions are not specified on the website, it is important to clarify that it has no statistical value”, says Janoni.

The major urban centers are precisely the places where women find work opportunities more easily since most of the female workforce is employed in the services sector. Nevertheless, the opportunities that Brazilian cities provide to each gender are still unequal since the very comings and goings of women are limited by this feeling of insecurity. The situation is most serious in the case of poor women who have to rely on inefficient public transport and often have to walk a good distance to the next bus stop. “Nearly 7,000 of the participants of the survey have changed what they wear for fear of being harassed. More than 6,000 have failed to do something they wanted or needed for fear of being harassed. We’re talking about women who do not have freedom of mobility through the city”, says Kenski.

For Kenski, the problem of catcalls is not limited to Brazil nor to underdeveloped or developing countries: “We are seeing strong campaigns against harassment in developed nations like the U.S. and France. It is clearly a global problem. Not by chance has UN Women launched a campaign against harassment”.

The argument that claims that restricting catcalls would undermine a Brazilian cultural trait is interesting because it conveys a point of view that sees culture as a static object that should be protected like a museum piece, when it is in fact changing all the time, adapting to the social practices of each period. When Brazil went from being a slavery society to a kind of equal one, hundreds of cultural habits had to be refurbished (in fact, we are still working on this transition). After all, slavery was not merely a social injustice separated from the rest of Brazilian social life: it was a mode of social organization that carried with it many social behaviors and cultural habits, just like sexism does.

Ending the gender violence represented by catcalls does not mean making the streets of Brazilian cities ascetic and impersonal. This is not the same as prohibiting spontaneous interactions and even public displays of affection and libido. The point is to give both men and women, both heterosexual and homosexual, the same rights to the city, the same right to demonstrate their libido in public in a respectful way. Today, catcallers are much more of a demonstration of power from an heterosexual man against any woman he considers desirable than a seduction game or a relationship starter.

When a man makes a compliment to a woman in a context in which a woman would never do the same, he is well aware he is intimidating her. When a man stops a woman who is obviously busy or rushed, he knows that he is intruding on her. He just decides to give his prerogative more weight than the woman’s needs, interests, will, and welfare. Catcalls are a very clear demarcation of gender positions: in the majority of the cases, what we see is a heterosexual guy approaching a woman and treating her as a sex object. Even the lexical choices highlight this strong genre background: girls passing by are called a “doll” or a “princess”, for example.

If the goal of catcalling really was to establish a legitimate approach to a possible sexual partner, one would expect this kind of compliment to happen in places and situations where people are typically eager to know one other. But it turns out that, according to the survey, it is more common for a woman to be “praised” while walking down the street than in a nightclub! Is it possible to admire a woman while ignoring her right to walk around town without being challenged by the spurious desire of others?

Not all cases are alike and sometimes approaching to a stranger in a square or on the subway may be fun and even a way of breaking the impersonal atmosphere of the big city. The big difference between flirting and harassing is that flirting is a subtle movement that stops when it does not receive a positive response from the other person. But, in general, street approaches are as impersonal as the city itself. The goal of this kind of approach is not to praise or even to establish a sexual bond, but rather to make clear to women that they may have left the home environment and are gaining ground in public and social life, but none of this will be easy.

Infographic: Online survey conducted in August 2013 with 7,762 Brazilian women by journalist Karin Hueck.

Infographic by Flávio Bezerra and Illustration “Walking in a public space does not make my body public.” by Gabriela Shigihara. Courtesy from the artists.

Tags: brazilian culture, catcalls, chega de fiu fiu, juliana kenski, karin hueck, Latin America, un women