The Resurgence of Regional Languages in Pakistan

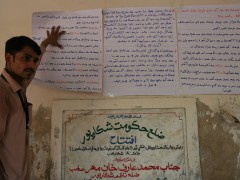

A training session in regional language on how to use a cheque — Photo by Oxfam on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Language and identity are so intimately linked that a person’s accent can also reveal which part of the world they come from! For instance, if she is speaking English or Urdu, a Pashto-speaking person can very easily be recognized as belonging to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province or any other area in Pakistan where Pashto is the dominant language. This is a recognisable fact as people from rural areas migrate to urban cities for better job prospects. Their different dialects are clearly noticeable.

In Pakistan the people speak many languages, including English, which have a direct impact on the cultural as well as the economic identity of the country. English is given preferential treatment because Pakistan was a part of the British colonial system. People give extra credit to those who speak ‘good’ English, since English-speaking people are seen as not only culturally sophisticated but financially sound as well. Unsurprisingly, English has always been an “aspirational” language in Pakistan because the job market demands candidates who are fluent in English, and English is also the official language of government and non-governmental organizations too.

Up to a few years ago in fact English was the preferred tool of communication at all levels: professional, social and personal. But a new awareness is now emerging that we should know and speak our regional languages (mother tongues) and represent our own cultural identity. People are starting to teach children their mother tongue before they start learning the national language (Urdu) and the academic language (English). I myself have a couple of cousins who have taught their children Pashtu and Kohati before Urdu and English. This new awareness is driven by the perception that many people like myself, whose mother tongue is Pashtu, are unable to understand and speak it. I find myself completely lost at family gatherings where I don’t understand what my relatives are talking about. And their children who are aged between 4 and 10, can speak four languages – Pastu, Kohati, Urdu and English – but can read and write in only two: Urdu and English.

My friend, Manal from the Chitral district in the northernmost area of Pakistan, is married to an Afro-American. Her daughters can also speak three different languages (Chitrali, English and Arabic) at the tender ages of 4 and 7. They speak Arabic because now they live in Egypt.

The happy fact is that this new awareness is spreading even though we have to speak English and be dressed (especially the men!) in western three-piece suits on official occasions. In their professional environment, the men, however, are allowed to wear Shalwar Kameez or traditional dress on Friday for religious reasons. It is a happy symbol which calls for a ‘return’ to our own cultural values and traditions.

The problem I have noticed is in the imbalance which occurs when you speak one specific language in a society like ours which is multilingual as well as multicultural. Students, for example, in order to get attention and show off speak in English inside and outside the classroom. This develops into a habit that leads them to forget their own mother tongue or regional language. Ideally, you might consider speaking English in academic and official settings but you should also make sure that you speak your own regional language so that the language won’t die out.

However, with the rise of this new awareness of our cultural roots, we are beginning to find our way in choosing where and when to speak a particular language. Obviously we will remain very much a ‘cultural mash-up’, but the patterns of living inside and outside cultural traditions are changing as we grow more sensitive to the importance of speaking our own regional languages.

Tags: culture, economy, jobs, languages, local, migration, pakistan, unemployment