Measuring the Influence of Internet Movements on Reality

“How the Internet Changes Our Reality” proclaims a vertical banner in front of the building of the Church of the Resurrection transformed into a ultra-modern Umweltforum venue hosting the Barcamp held by Future Challenges, the Club of Rome and the Berlin Institute for Internet and Society.

Ironically speaking, one might say that the chosen venue automatically implies that the “Internet’s abilities to change reality are God-like.” But is it really so?

The complexity we can’t yet measure?

The Internet has changed the way people organize their memory (and particularly outsource it to Google spiders), organize themselves en masse (thanks, Ushahidi developers for crowdmapping and Egyptian activists for Tahrir-like city planning), and do many other things.

But can we say what exactly has changed? I mean, obviously we can feel a paradigm shift taking place, but the question how to measure this shift remains unanswered.

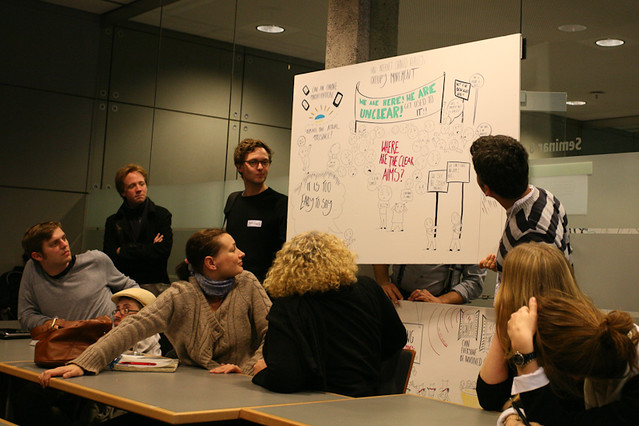

Internet-driven phenomena such as new mechanisms of collaboration and networked leaderless movements, however, are complex and involve lots of drivers. As a result, by the end of the Barcamp, the participants had discussed everything from “Occupy Wall Street” and the Tea Party movement to structuring data chaos and crowdsourcing but were still not able to answer how the success of digital movements in driving change was to be measured. One of the main reasons for this lies in the difficulty of understanding what digital movements are in the first place.

Occupy Wall Street – not a movement at all?

Several directions of thought were presented at the Barcamp:

1. Digital movements are too young to be analyzed and there’s not enough empirical data to make conclusions. As one of the participants noted, OWS is just 6 months old.

2. To understand digital movements we need to improve our methodics. As one of the participants said,”In order to understand the Occupy Wall Street movement we have to de-complex it, de-code it and make it more simple.”

3. What we see as movements are not movements at all.

The last option needs further scrutiny. A part explanation is provided in these quotes: “The Occupy movement provides an opportunity if you have an issue” and “OWS is mirroring the general confusion with the system, it’s like a system fail. This is exactly why it doesn’t have any concrete goals.” In other words, there’s no way to measure the network-driven movement since it’s an environmental phenomenon, not a social movement in the traditional sense with its aims, ideals, symbols and martyrs. As one of the OWS slogans says: “We’re here, we’re unclear. Get used to it.”

The View from Russia

In the country where I come from digital reality is pretty different from what is shown on TV or reflected in publicly allowed discourse. In a state with a hybrid semi-authoritarian, semi-democratic (although much more autocratic than democratic now) make-up, discussions on the influence of change are ongoing. Cyber-sceptics often point to “slacktivism” – or lazy Internet-only activism of likes and re-tweets – as the measure that is comfortable for the authorities and simply becomes a safety valve for letting off steam.

My personal view is that networked movements do indeed have an environmental nature. This means that their effects a) are long term, b) are significant and hard to notice at one and the same time.

To illustrate my thesis, here are few examples of how networks influence politics in Russia.

The invisible hand of networked discourse

According to the Levada Center, in October 2011 the popularity of the “United Russia” party dropped 9 percent from 60 percent to 51 percent. Other ratings (support of Medvedev and Putin) also declined. Obviously, these changes might be due to a variety of factors so the Internet’s alternative discourse could only be one of many.

However, given that Russian TV channels do not allow even less controversial topics, where do people go to get the alternative? Considering there’s still a partly free and hard-to-control online environment, people can always get alternative views via their TCP/IP connection.

The effect of the networks is limited though. At the start of the year 6 percent knew who Alexey Navalny, an anti-corruption blogger, was. 33 percent, however, stated that they would agree with the slogan “United Russia is the party of crooks and thieves”, invented by the same blogger. This is important since this slogan was distributed solely via blogs, radical newspapers and word of mouth.

One story in wide circulation is of president Medvedev’s visit to the Journalism Faculty of Moscow State University during which several bloggers were detained while the president held a press conference with a set-up crowd. And it got out despite the fact that the NTV channel refused to give any coverage to the story, effectively closing down the TV channel of communication. Yet as another Levada Center poll says, 29 percent of the population somehow found out about this episode. Although it was a storm on the blogosphere, a TV-viewer would hardly have heard a squeak about the scandal.

Even so, many Russian opposition politicians are rather cyber-sceptical saying that digital activists won’t go onto the streets in support of their ideals. What they miss is that the Internet, even without creating mobilization advantages, still plays an important role in fixing the lack of a place for the marketplace of ideas.

***

While in Western countries where the media environment is much freer the ability of networked movements to provide change is more subtle and even harder to measure. So the true answer to “How Internet changes our reality” would be, “Check out your news in 5 years time and you’ll see.”