Thinking Europe’s 1st World Problems

European think tanks held their big annual shindig this week at the Brussels Think Tank Dialogue, including not only those of the EU bubble, but also major national organizations such as the French Institute for International Affairs (IFRI) and the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

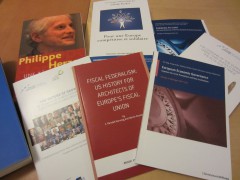

On display was the incredible output of reports and documents from Europe’s political research institutes: from booklets comparing EU vs. U.S. fiscal federalism to meaty collective tomes such as that on ensuring “Competitiveness and Solidarity in Europe”. Wonk heaven must look something like this.

Think tanks have an odd place in society. Neither cloistered like a typical university (the adjective “academic” being contemptuous when qualifying a debate), nor directly acting like government, at their best they aspire to be something like Antonio Gramsci’s organic intellectuals: providing the theory and analysis behind what one hopes is coherent action.

The issue du jour was naturally the economic crisis and the conference itself was held under the rather somber banners of “Solidarity of Austerity”. These, while mentioned, did not monopolize the discussion. The events’ expert workshops focused partly on the alarming economic situation, but also on the Schengen free-travel area, the EU budget (€147.2 billion this year), the Arab Spring, and increasing resource efficiency (e.g., better use of oil, metals…).

The proposals were rarely dramatic, but rather, incremental. Revolutions are rarely possible in European policy. Volker Perthes, director of the SWP, advised direct engagement between the European Parliament and civil society and democratic organizations and politicians in post-revolutionary Arab country. It’s doesn’t have the spectacle or drama of a war but it sometimes it might just work better. “We know that our foreign policies are very much structural and long-term,” he said.

This might seem underwhelming as Europe faces a double-dip recession and harsh economic dislocation in many countries, but the continent’s life goes on despite the crisis and, when one talks of being a bad state, it’s good to remember everything is relative.

Arif Havas Oegroseno, Indonesia’s Ambassador to the EU, was perhaps the most upbeat. He recalled that the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, little-remembered today, had been similar in some ways to that which Europe now faces. It had shorn years of growth from traditionally booming economies and almost halved the values of the currencies of South Korea and several Southeast Asian countries. Even Greece’s debt today, at a whopping 140% of GDP (and rising), is still less than that reached by many of these countries in the 1990s.

In Indonesia, there had been an 80% drop in the currency value, drought, and a looming threat of separatism among the country’s over 200 million people spread across innumerable ethnicities and some 17,500 islands. Yet today the country is relatively stable and its economy is growing steadily. The diplomat advised optimism: “If I compare what’s happening in Europe today to the situation in Indonesia in 1998, this is just a walk in the park.”

It serves as a reminder as to whatever problems Europe has, these are for the most part First World Problems (explanation), that are nothing like the poverty and violence endemic in other parts of the world (or for that matter, the tragedies of Europe’s not-so-distant history and those remaining in Eastern Europe). Europe, in all its achievements and contradictions, is continuing to develop as a unique continent. On this one of the books presented had a particularly appropriate title: Une tâche infinie, An Endless Work. It continues.

Tags: Brussels, euro crisis, European Union, Think Tank Dialogue