Regional Solutions to Biodiversity Conservation

Biodiversity conservation is an urgent matter worldwide. Ecosystem loss and degradation have become pressing issues globally with thousands of species becoming threatened or extinct each year, often in the name of development. From the early 1970s, several conventions culminating in strategic reports or plans have promoted awareness and action for sustainable development. Examples include the Club of Rome, the WCS, the UN Convention on Biodiversity, the Brundtland Report, Caring for the Earth, Agenda 21, the World Summit on SD, and the MEA. It is worthwhile to take a closer look at the efficacy of these costly global conventions and their outputs to see if they are indeed having an impact on serious environmental issues at the local level. Are international conventions necessary, or should the legwork be done at home?

Australia is widely recognised for its rich biodiversity and for its multitude of unique and endemic species, and therefore has a keen ecological, social and economic interest in biodiversity conservation. Australia was of the first countries (1996) to comply with Article 6 of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, which called for the development of national action plans or strategies with the goal of “integrating conservation and the sustainable use of biological resources into national decision-making and mainstreaming the issue across all sectors of the national economy and policy making.” Australia often acts in accordance with global environmental conventions.

When it comes to sustainable development and biodiversity conservation, most people immediately think of species biodiversity (Save the Whales!). Yet other types of biodiversity conservation are equally important, including genetic biodiversity within and across species and whole-of-ecosystem biodiversity. The Nature Conservation Act of Queensland (1992) identified these levels of conservation and additionally noted the importance of regional biodiversity conservation. A reduction at any level of biodiversity equates to a limitation of potential for adaptation to change. This is exacerbated by rapidly changing environments which many now claim to be the result of climate change. However, climate change skeptics and adherents alike acknowledge the importance of biodiversity conservation regardless of the cause of the loss/degradation of species and ecosystems. A front-runner in environmental action, the Australian Government recognised this threat and addressed the potential implications of the changing climate in the 2006 State of the Environment report. This document stresses the importance of local level environmental action.

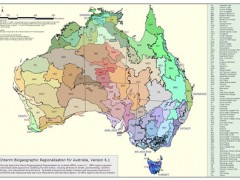

In the last two decades there has been a fundamental shift in the Australian government’s approach regarding environmental management. The fact is that ecosystems do not conveniently stop at state borders or fit into other arbitrarily drawn boundaries, therefore a unique approach to biodiversity conservation was necessary. Previously the State government held the primary role in land management, but these services are now increasingly decentralised and replaced with a more targeted and collaborative approach. Increased investment by the Federal government has funded programs such as the National Heritage Trust and the current program Caring for our Country, which involves cooperation between the three tiers of government and encourages community engagement through Environmental Stewardship service packages. Through these packages, thousands of community groups and private landowners have received funding for environmental and NRM projects in their local areas. An emphasis is placed on partnerships between local government and civic organisations, which is thought to increase the likelihood of securing funding for small, medium and large-scale projects. Any stakeholder with an idea and a plan can apply for this funding, designed to address the larger issues by tackling one smaller issue at a time.

Thus, conservation measures such as improving water and soil quality, erosion and invasive species control, and catchment restoration are increasingly undertaken by private landowners, community-based groups and regional natural resource management (NRM) bodies. There are now 56 regional NRM groups who are responsible for developing unique regional management plans. Collective NRM groups also undertake monitoring and evaluation to measure program/project success.

Critics warn that there are wide variances in the capacity of local governments and regional groups to adequately undertake and fund projects in their respective regions. There is concern that bioregions of lower priority will ultimately suffer or be passed over entirely, as funding focuses on high-priority and/or politically and economically strategic locations (such as the Great Barrier Reef). Regardless, the involvement of landowners and local stakeholders in the conservation of their own regions marks a definitive shift from the previous top-down strategic frameworks of conservation governance.

So, can overarching international frameworks for biodiversity conservation possibly address unique local issues? Regional solutions seem much more appropriate in the Australian context. International conventions which culminate in prescriptive reports may serve to steer local action, but ultimately context is king and can not be overlooked or underestimated. Global frameworks are too broad to address local contexts, unless used only as signposts to support local stakeholders and regional NRM bodies in addressing their own pressing issues. Australia has the resources and collective will to progress with biodiversity conservation strategies, even in the absence of any future global conventions.

Tags: australia, BIODIVERSITY, Bioregion, CLIMATE CHANGE, democracy, ENVIRONMENT, Natural Resource Management, Queensland, regional