Resource curse or blessing: mining and Aboriginal communities in the Pilbara

Initially, the thought of large-scale mining in Australia saddens me, imagining the inevitable scar it will leave on the landscape. Although I am not an indigenous Australian, I can imagine this sentiment must be much stronger for peoples who believe they do not own the Earth, but rather, they are caretakers of the Earth, their Mother. Considering there can be no stopping the mining boom, however, it is at least heartening to see several mining companies who are leading the way in corporate social responsibility, demonstrated by a range of negotiations with Aboriginal communities to ensure they benefit from mining operations in the long term.

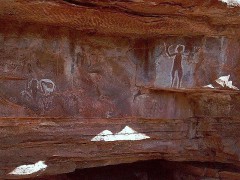

The Pilbara region of Western Australia is a stunning landscape of rocky hills, adorned by as many as 1 million images of rock art engravings. Sadly, a significant portion of these have already been damaged by mining. Clearly, mining giants in this region must make a greater effort to respect the rights of indigenous peoples if we are to preserve this cultural heritage for future generations. Negotiating with indigenous communities, however, means more than just royalties, which often lead to dependency or the “resource curse” as experienced in many developing nations. In recent years, several extractive industries have begun to engage in partnerships or joint enterprises with Aboriginal businesses and communities.

Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton pay approximately 0.5% of royalties to Aboriginal communities in the Pilbara region, as well as preserving sacred sites while expanding employment and training opportunities (Rio Tinto now employs 1600 indigenous workers). One indigenous community, however, is outstanding in its efforts to achieve a breakthrough agreement with one mining giant, Fortescue Metals Group.

Recently, the Njamal people of the Pilbara region signed a breakthrough agreement with Fortescue that will make them managers of a mine with the potential to produce 100 million tonnes of iron ore, worth tens of millions of dollars.Under the deal, the Njamal will mine the ore on the tenement covering 847 square kilometres of their native title claim and Fortescue will buy it at an agreed price on top of an annual management fee. While several of the elders expressed regret over the impact the mine will have on their land, they also acknowledged the potential benefits it can bring to the younger generation, particularly in terms of employment opportunities. Moreover, it is a long-term partnership, not just a once-off deal.

Meanwhile, the Ngarda Civil and Mining Pty Limited was formed for the specific purpose of providing Indigenous Australians of the Western Australian Pilbara Region employment and training opportunities within the civil and mining industries. The group strives to maintain an indigenous employment rate of 50% at all times, and partnered with BHP Billiton in 2009 to launch the Purarrka Indigenous Mining Academy (PIMA).

These “success stories” demonstrate the potential of mining agreements, when considered thoughtfully and respectfully, to benefit Aboriginal communities. Notwithstanding, there continues to be a lack of government policy on the matter. According to Paul Cleary, Research scholar at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (ANU), the success of the abovementioned examples has been in part due to Native Title Law, in part due to a changing corporate culture, and mostly due to the perseverance of indigenous communities to stand up for their rights. Initiatives such as Publish What You Pay are also playing an important role in promoting the transparency and accountability of extractive industries world-wide.

It is easy to romanticise indigenous communities and say that they absolutely reject the idea of mining. While for some communities this may be true, I would agree with Andy White who says that most indigenous communities do want to share in the benefits of mining – but on their terms. Or in the words of Jody Broun, co-chairwoman of National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, ”We want Aboriginal people to be able to negotiate from positions of power with extractive industries.” My hope is that governments and NGOs around the world will help raise indigenous communities into similar positions of power, in order to give them a fair chance of negotiation when confronted with mining giants.

Tags: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI), Aboriginal Rights, australia, BHP Billiton, Fortescue Metals Group, mine, mining, National Congress of Australia's First Peoples, Native Title, Ngarda Civil and Mining Pty Limited, Njamal people, Pilbara, Purarrka Indigenous Mining Academy (PIMA), Resource curse, Resource Management, Rio Tinto, royalties