North Korea’s Public Health Problem

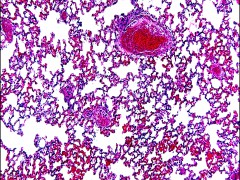

In 2010, the prevalence rate of tuberculosis in North Korea was 399 per 100,000 people. This is alarming given that Ghana, another developing country with the same population of 24 million, has a prevalence of only 106. The amount of infected individuals is more than three times higher than that of South Korea and China. The situation in the country only compounds the problem, as even 20 years after a famine reportedly killed about 3.5 million people, malnourishment is still rife, and a weakened body increases susceptibility to the disease.

However, North Korea’s history with international agencies and non-profit organizations to target the elimination and prevention of this disease has been positive. One victory was the construction of a laboratory which has the capability to diagnose drug-resistant TB strains. This idea was formulated in early 2007 by John Lewis, a professor at Stanford University, who considered engaging with North Korea by helping them with their TB epidemic. Given the infectious nature of TB, this was undoubtedly a matter of international interest, and it received much positive reception worldwide.

Collective Cooperation

Public health officials from North Korea and experts at Stanford University met several times, initially at Stanford and then later in Pyongyang. The project, led by epidemiologist Sharon Perry, was named the US-DPRK Tuberculosis Project, and its success was the result of collaboration between Stanford School of Medicine, Christian Friends of Korea (a U.S. non-governmental organization), the WHO South-East Asia Regional Office in Delhi, and North Korea’s Ministry of Public Health.

The willingness of North Korea to engage with international academics and specialists is a good sign. A grant from the Global Fund has cured 31,000 TB patients in North Korea since 2010, achieving the second highest performance rating available. The Eugene Bell Foundation, a non-profit organization registered in both South Korea and the US has also worked with North Korea for over 50 years to help control their TB epidemic.

International Interests

The international community must continue to support North Korea with this issue, as the consequences of ignorance are potentially catastrophic. If a drug-resistant strain unresponsive to current drugs were to evolve in North Korea, it could easily spread rapidly through the small channels of tourism and trade, as well as the sporadic flow of defectors across the border with China. It is problematic that public health is routinely left out of any sort of discourse on North Korea. However, throughout the upcoming year, as countries with or without formal international relationships with North Korea re-evaluate their diplomatic stances, policy makers should keep in mind the dangers of ignoring the state of the health system.

Involving public health in foreign policy is complicated, especially when it involves a process as delicate as persuading North Korea to phase out its nuclear capabilities. However there have been cases of success; for example Brazil’s exportation of its successful HIV/AIDS combating model to other developing countries has increased its access to international markets. At the very least, employing healthcare diplomacy in North Korea through official channels is a useful way of showing compassion to a people who are taught as schoolchildren that contact with the outside world should be avoided. It would be a small but positive step towards effective engagement with North Korea, one of the world’s most isolated countries, and could potentially cause negotiations to end more positively than they have done in the past.

Ye jin Kang is a member of Global21, a student network of international affairs magazines and a partner of FutureChallenges. A longer version of this article was first published in The Oxonian Globalist.

Tags: Healthcare, tuberculosis