Death Threat

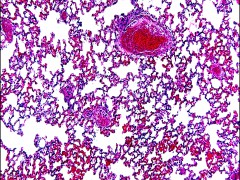

Barely 20 years old, Israel has already been fighting cancer for two years. But his troubles don’t end there; excessive radiotherapy administered at a Mexican hospital caused a necrosis of the brain and he has lost his sight. His treatment proved ineffective, so now he’s spending his final months in darkness. If he had received the correct treatment, he could possibly be living a normal life and enjoying a few healthy extra years. But his blindness is an unnecessary burden, caused by an ineffective system struggling under increasing demand, excessive bureaucracy and lack of funding.

Barely 20 years old, Israel has already been fighting cancer for two years. But his troubles don’t end there; excessive radiotherapy administered at a Mexican hospital caused a necrosis of the brain and he has lost his sight. His treatment proved ineffective, so now he’s spending his final months in darkness. If he had received the correct treatment, he could possibly be living a normal life and enjoying a few healthy extra years. But his blindness is an unnecessary burden, caused by an ineffective system struggling under increasing demand, excessive bureaucracy and lack of funding.

The Inverted Solution Paradox

Israel’s situation is just one example of the inefficacy of the healthcare system when dealing with non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The chronic nature of NCDs such as diabetes, cancer and respiratory and cardiovascular conditions is leading us into a seemingly unsolvable paradox: each time a patient is treated, if they are not entirely cured, the number of diseased people increases. Dr. Brian Druker, creator of a drug that extended the lives of patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) by up to 30 years, has noted the irony at the heart of his work: “I’ve achieved the perfect goal inversion of oncological medicine; my drug has increased the prevalence of cancer in the world.” Before the invention of his drug, AML was a relatively rare disease because patients could only expect to live for three to six years after treatment. Today, AML has become far more common, and, according to Hagop Kantarjian, quoted in A Biography of Cancer, it is expected that within the next 10 years there will be at least 250,000 people living with the disease in the USA alone thanks to direct therapy. Declining death rates and an aging population will soon place a huge economic burden on low- and middle-income countries that cannot assure a healthy aging process or continuous and coherent treatments of these diseases. In many countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, the economic burden of diabetes is typically between two to four percent of GDP. At the same time, between one to three percent of GDP is spent in developed countries for treating cardiovascular diseases, and a similar percentage is spent annually in China on tobacco- and obesity-related diseases. According to the World Bank’s Human Development Network, 43 percent of the 23.6 million people who died from NCDs in low- and middle-income countries in 2005 were classed as working age (15-69 years old). In these cases, the economic burden isn’t derived solely from the outstanding medical expenses and the loss of productive hands in the country, but from thousands of families that fall into poverty while trying to pay the incredibly high price of fighting a chronic disease.

An apple a day keeps the doctor away

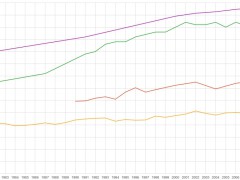

Today, NCDs are the main cause of death in most countries except for the African region where communicable diseases are still more deadly. According to data provided by the Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases 2010, of the approximately 57 million deaths that occurred in 2008, 36 million were caused by NCDs. And these numbers are increasing. It is expected that within the next 10 years the number of deaths related to NCDs will increase by approximately 15 percent globally. Of course, such an increase would be disastrous, both economically and socially. The amount of money required to speed up research and keep pace with this growing number of patients is simply not viable for countries that are barely able to cope economically. Faced with such a situation, it can no longer be a question of finding new treatments and reaching the poor with miraculous solutions. Millions of lives, tens of millions of years of quality living and billions of dollars can be spared by adopting a policy that combines treatment with prevention and early detection. Although it may be impossible to reduce the total number of NCDs in the coming years, experts believe that with the proper preventive efforts, it is possible to slow the increasing death rate from six million extra deaths to around three million in the next 10 years.

Prevention and policies

Creating policies to slow the rate of NCDs isn’t easy. It is necessary to consider both the causes – consumption of tobacco and alcohol, unhealthy diets, lack of physical activity, reduced sleeping hours – and the social processes that give rise to the increased risk factors. In the small town of Framingham, Massachusetts, where the connection between cholesterol and heart attacks was first made many years ago, scientists have been studying the effect of social interconnections in the recurrence of habits such as smoking. The results indicate that these interactions actually define the habit of smoking, meaning that to beat the habit it is necessary to modify not just the individual but their whole social structure. This is the reason why successful health policies must consider a mixture of direct and indirect long-term measures if they are to succeed. In the case of tobacco, for example, it took developed countries many years to adopt policies that would drastically lower the number of smokers. Compare that to the situation in developing countries – where the proportion of men who smoke has increased from 30 percent to 50 percent in the last 20 years – and it’s clear there is much work to be done. It is essential that developed countries set a positive example on this issue, especially in the face of marketing initiatives that many in the West find unacceptable. China’s Project Hope, for example, has opened the doors to primary schools receiving financial help from tobacco companies, prompting commentators to rail against cigarette companies pursuing the next generation of smokers at such a young age. But we shouldn’t be fooled into thinking that the rampant spread of NCDs is a problem exclusive to the developing world. Obesity was first considered an epidemic in the USA in 2000, and it costs the US government around $117bn each year. A domino effect has been noted and now Latin America (primarily Mexico) is facing the costs of the non-prevention paradigm. In January last year, Mexico took the USA’s oversized crown to become the country with the highest rate of obese and overweight people, and now spends more than 11% of its total annual health budget (.5% GDP) on tackling the problem. If there’s any chance of cushioning the huge impact of NCDs, it will be necessary to work with the three main points of economic growth, prevention and direct medical care. Low- and middle-income countries will need to apply their limited resources cleverly and take advantage of the aid given by multinational institutions and developed countries. Only self-sustaining solutions will prevent the disastrous effects of an overburdened healthcare system.

*Photo taken from user koadmunkee on Flickr, CC BY 2.0Daniel Kapellmann is a member of Global21, a student network of international affairs magazines and a partner of FutureChallenges.