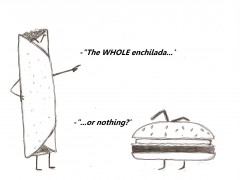

The Whole Enchilada

9/11 not only changed American discourse on security but also modified the US- Mexican relations and with it its promises of a fair accomplishment of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) regarding immigration and trade.

“[There is] no more important relationship in the world than the one we have with Mexico,” said former US President George W. Bush when he welcomed former Mexican President Vicente Fox on a visit to the US. “…A relationship of unprecedented closeness and cooperation. And this visit is a milestone on that journey.” It was September 4, 2011.

Back then, Vicente Fox embraced his role of Mexico’s first opposition President after ending 71 years of one-party rule. Confident enough, he demanded that the US Congress give Mexican migrants “their proper place in history” by pushing over a possible amnesty for an estimated 3 million illegal Mexican immigrants in the US by the end of that year. This was after Mexico’s former foreign minister Jorge Castañeda obtrusively stated before a gathering of mainly Latino union members that the Mexican government was going after the “whole enchilada” on immigration, stepping up the stakes on this debate.

In spite of the Republican Party’s opposition, Bush considered this strategy as an opportunity to increase the Latino electorate above the 35% he had captured in 2000 to go after the 2004 re elections. Mexico was in the spotlight of the US’ and it seemed though as things were starting to look up for Vicente Fox after his first state-of-the-nation address when he appealed for more time to live up to the promises of change that got him into office.

But a week later after Bush and Fox’s first meeting, the 9/11 terrorist attacks made the Mexican topic almost irrelevant to the American agenda, one that quickly focused its policies on Afghanistan and Iraq. That pursuit of going after maybe just a mouthful of that “enchilada” was put on hold for an indefinite time.

Since that day, the security subject has preponderantly imposed itself in the bilateral agenda of these two countries, especially over the war against drug-trafficking and terrorism.

The US-Mexico border was already regarded as a security subject even before the 9/11 events and has served a purpose since then to overlook agreements and provisions stated in the NAFTA, such as the free travel of Mexican trucks on US highways.

The NAFTA agreement calls for the fast crossing without delays over the border for the Mexican auto transportation; however, the US has failed to fulfill these, claiming that Mexican trucks are not safe enough. Economic barriers were brought down under NAFTA but security barriers became more sensitive when instaurations of high alert level and permanent intense inspections were held provoking prominent commercial traffic disruptions that affected deliveries, border retail sales, and tourism. The US and its neighboring countries negotiated Intelligent Borders to prevent more future disorders on border trade, secure infrastructure and people, as well as goods over the North American borders.

However, concentrated flow on the limited entry ports provoked inefficiencies negatively affecting local, state, and national economies in Mexico. Add the lack of proper investment in the border infrastructure in comparison to the increase of trade and people flow to the long waits and delays due to the extra security measures since 9/11. This adds up to a 7- 17 hour wait on the border which translates to an increased cost of crossing northbound, and 10-20% of the total costs of Mexican transportation.

After 9/11, any crossing through the US-Mexico border became a matter of security, especially immigrants. The exacerbation of the nationalist sentiments provoked by the 9/11 events unchained a xenophobic trend that regarded all foreign element as a potential threat to US national security. This made it easier for the US to pass bills like the Patriot Act, which backfired on congressman Sessenbrenner’s immigration policy proposal. This unchained protests across the US during the spring of 2006 organized by local migrants, Mexicans as well as other foreigners, who protested against clauses like the one granting faculty to any policeman in the United States to arrest and immediately expulse from American territory any foreigner only by its simple appearance that would look like an illegal alien.

Participants during the rallies carried banners with the slogan: “Today we march, tomorrow we vote.” And so in 2010, we know they did. The Latino vote, two thirds of which is represented by citizens of Mexican descent, was crucial for Barack Obama’s first presidential triumph and these past elections.

It would be highly misleading to state the US-Mexican relations have become completely frayed and relegated, but the security subject has clearly been imposed over the American agenda affecting the Mexican interests.

Congress still opposes Obama’s 2012 Executive Order stating that “people younger than 30 who [went] to the US before the age of 16, pose no criminal or security threat, and were successful students or served in the military can get a two-year deferral from deportation,” which will allow the US to concentrate its resources on illegal immigrants that represent real security threats.

The question is not whether to keep the borders safe or not, but how to better manage the discourse revolving immigration which has been wrongfully narrowed down to security measures. The deportation of 296,906 illegal immigrants in 2011, the largest number in the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency’s history, supports this.

Not only did the Mexican government have to forget about getting that piece of the “enchilada” on a joint work project on immigration policy, but both Fox and Jean Chretien lost any chance they once had to advocate the idea of free flow of people, especially workers, across the US north and south border as a second phase of NAFTA like it originally intended to.

It seems that Mexico, as well as the US, lacks the will and imagination to incorporate in a more constructive way each of their own grand designs on national policies to the asymmetric interdependence within the legal framework created by the NAFTA. It will be hard, though not impossible, to combine an acceptable sovereignty to Mexico with a border security outline that is convenient to the US, and then work from this basis, on the international part of a revitalized national Mexican project.

Mexico has been conditioned to its own narrow limits within its development model and to its profound international crisis revolving the drug war within the country. A new border model could be negotiated, with a preliminary agreement to eliminate all external commercial barriers still present in the region, as well as a new closer collaboration agreement on security.

Also, a political consensus needs to be built in Mexico. One that is capable of allowing a coexistence of both the right and left wings’ foreign policy principles, crafting a pertinent direction in its national project and be clear as to exactly which “enchilada” it is going after.

Bere Belmares is a member of Global21, a student network of international affairs magazines and a partner of FutureChallenges.

Tags: 9/11, aftermath, Barack Obama, Congress, enchilada, free flow, George W. Bush, immigration, Jean Chretien, Mexico, NAFTA, trade, US, Vicente Fox