What Is Civil Society, Anyway?

Biscuit Theory was a flash in the pan. It erupted as an attempt to explain why and how civil society organisations (CSOs) work together, and disappeared just as quickly in a puff of their own transiency. Its simple claim was that the extent of CSO cooperation correlates directly to the supply of biscuits in a given context. Not only are biscuits crucial to the conduct of all CSO meetings but they are also an indicator of the kind of politico-economic stability required for cooperation.

I invented Biscuit Theory during a particularly unproductive meeting with a CSO in which I had little to do but ensure the arrival of other, more important participants. It did not catch on, and I had forgotten about it by lunchtime. However, understanding the factors that permit and encourage cooperation within civil society is of vital importance in order to promote the positive outcome of cooperation between CSOs.

The idea expressed in The Greater WE that civil society and global governance can intersect at the point where governments fail to act is optimistic. Unfortunately, what we call “civil society” is far too fractious to achieve large-scale cooperation. We should focus on small areas of co-activity along the lines of geography or common areas of expertise.

The challenges are particularly severe in the Middle East where those organisations and individuals that make up civil society are often vehemently opposed in their interests, agendas and ideologies. Where there is a paucity of public goods – and particularly accountability – the potential for private interests and political expediencies to be played out in the work of civil society is considerable.

To avoid getting our knickers in a twist, it is first necessary to ask, “What is Civil Society?” This question is essential if we are to understand how to achieve any cooperation amongst its various and disparate factions in a world where cooperation is a scarce commodity.

The general definition of civil society that is thrown around without much consideration is, “stuff which isn’t the state and isn’t business.” Another idea behind the common usage of civil society is of “people doing things because of a cause.” Some people even capitalise Civil Society.

A more exhaustive definition of civil society penned by the Centre For Civil Society at London School of Economics runs as follows:

Civil Society is the arena of un-coerced collective action around shared interests, purposes and values. In theory its institutional forms are distinct from those of the state, family and market; though in practice the boundaries between state, civil society, family and market are often complex, blurred, negotiated and evolving. Civil society commonly embraces a diversity of spaces, actors and institutional forms, varying in their degree of formality, autonomy and power.

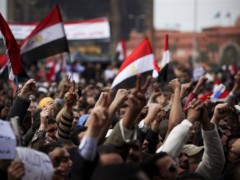

This definition is right to emphasise the varying institutional characteristics of civil society, because we use it to include international aid organisations with distinct activities, funding and employment, as well as mass movements such as those which are now occupying cities around the world.

The word “un-coerced” is also problematic, because many members of what we would generally describe as civil society organisations (CSOs) take part in an employer-employee relationship. In return for their (sometimes considerable) salary, they are expected to follow instructions from the senior management of the organisation and carry out activities according its agenda, not their own. Moreover, we often deal with things that may look like civil society but are in fact not functionally or instrumentally part of the layer between state and individual insofar as they represent narrow, rather than public, interests – a key example here is the prominent role played by private political interests, such as those of Islamists groups, in the Egyptian revolution.

The Arab Spring is indeed a source of considerable confusion as regards civil society and the exercise of non-state governance. For example, the president of the Kiel Institute of the World Economy Dennis Snower claims that: “There are different forms of global governance that we are beginning to feel more powerfully and the Arab Spring is the last example of this, and this is soft global governance. This does not come top down, it comes bottom up. It is enabled by new technologies, also the social media, that permit people to participate in their own destiny to a much larger degree than they ever were able to do before.”

Snower is correct to point out the importance of new technology and the radical nature of emerging mass movements in the Arab world. However, the idea that the Arab Spring is a movement with a coherent motivation ideology or function – or indeed that it exhibits anything like “soft global governance” – is a pervasive yet fallacious one. Many politicians, including in the US and UK, herald an “Arab Awakening” and forward the notion that people are empowered to push for democracy and for their rights.

The Arab Spring has not exhibited any form of civil society cooperation (not even with capital letters), nor has it shown any level of governance – global or national. It is not 1989 in the Middle East. This is not to say, however, that the outcomes are negative – it is possible that countries beyond Tunisia will reap the positive rewards of democracy and bolstering human rights. But as it currently stands, the only outcome of the Arab Spring which can be called ‘governance’ is the recent election in Tunisia of a body to construct a new constitution. This has been carried out with the assistance of international organisations and observers under the authority of the Tunisian army. It is in fact a fairly old sort of governance. Similarly, in Egypt, new elections – again run by the national army – will provide an elected chamber capable of performing some governance functions.

The chain of events that removed dictators in the Middle East did involve mass action by numerous organisations mobilising support with new technologies. However, it does not take cooperation to re-tweet the time and location of a rally. The fractious nature of opposition in every single state affected by the Arab Spring and their constant infighting suggest that for established grass-roots political movements – most probably falling under our definition of CSO – are conducting a power grab.

It is vital not to deceive ourselves. The power of street movements has been proven in the freedom-promoting expulsion of dictators and – partially – their regimes. However, there is no evidence that governance has improved. The conflicted nature of civil society means that greater cooperation is very difficult to achieve.

The solution is to focus on small scale cooperation and fostering individual relationships with a view to building CSO coalitions on matters where they share interests and can combine resources.

Tags: arab spring, Civil Society, democracy, economy, egypt, Global Governance, middle east, Technology