When Ethnos Decides, Not Demos

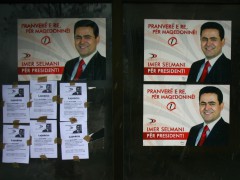

How long will Macedonians have to wait for a true non-ethnic approach by politicians? Imer Selmani, an Albanian candidate for Macedonian presidential elections got support from voters of all ethnic backgrounds. Photo by Tramonte on Flickr. CC BY-NC 2.0

When voters go to the voting booth they think which candidate offers the best program for education, the lowest taxes, the best pension system, the most reliable healthcare system, the economic policies that ensure low interest rates, safety in the streets, etc. We might assume that voters in Macedonia face the same dilemmas. After all, they know they live in a democracy and have the freedom to choose from a variety of parties all desperate to win their votes. They hold the power to determine which political party will govern the country for the next 4 years. Only there’s a little problem in the pre-selection process.

And that is, their choices are ethnically predetermined.

They are probably not even aware that before they evaluate the various electoral programs, before they decide who is more left, more right or more center, they have as a matter of course eliminated all parties of different ethnic origins to themselves. This is not a one-sided decision. Ever since 1991, political parties in Macedonia have been established as ethnic parties and are only interested in the votes of their own ethnic communities. The largest ethnic community is the Macedonian, comprising 64.2% of the population, followed by the Albanians (25.2%), Turks (3.9%), Roma (2.7%) and some other smaller ethnicities (4%). When parties win elections, they ‘govern’ in those areas where their ethnic community is dominant. This means that if an ethnic Macedonia politician is appointed as Minister of Culture, she will sponsor building of Macedonian monuments and sculptures, she will fund theater plays in the Macedonian language, and she will renovate Houses of Culture predominantly located in areas where ethnic Macedonians live. And the situation is much the same if an Albanian takes the same position: her attention will be focused on promoting Albanian culture, so she consciously ‘forgets’ the Macedonian, the Turkish, the Roma…

This ethnic division in governance has been an unwritten rule in Macedonian politics for a long time. Yet in 2009, there was finally a chance for change when Imer Selmani – a successful Albanian businessman who had an even more successful term as Minister of Health – ran for president. The high approval ratings achieved during his term in office went beyond ethnic lines and were confirmed by the elections which showed voters of all ethnic backgrounds supporting him. Everybody was enthusiastic about the appearance of the Macedonian ‘Obama’. He came third in the elections, outstripping four other Macedonian and Albanian candidates.

However, Selmani failed to make the grade as a change-maker. His newly established New Democracy party took on an aggressive nationalist Albanian rhetoric; nationalist right-wingers took over his party and instead of becoming a leader who changed mind-sets, he let their viewpoints change his own positions. Instead of offering the new economic programs desperately needed by citizens of all ethnic backgrounds, he merely propagated radical Albanian stances. Not only did he alienate his non-Albanian supporters, but also limited his offer to the Albanian electorate, most of which was already divided up between the dominant Albanian parties, the Democratic Union for Integration and Democratic Party for Albanians.

So, in between the ethnic divisions of politics and society, are we building a democracy or an ethnocracy in Macedonia? An ethnocracy has already been built, that much is evident. Managing the ethnic and religious diversity of the Macedonian society requires a political vision which transcends ethnic lines. The continuous reinforcement of ethnic interests in the political sphere only serves to exacerbate division and undermine democracy. When in opposition but especially when in power, parties need to look beyond their own ethnic constituencies and see the demos, not just the ethnos. Certainly, this is not the only problem of Macedonian democracy, but one that is of grave importance for this multiethnic country. Political parties in Macedonia are apparently not, but should definitely become, students of Italian political scientist Giovanni Sartori who teaches that in a democracy a political party must be “capable of governing for the whole”.

Tags: demos, elections, ethnic cleavage, ethnicity, ethnos, fyrom, imer selmani, Macedonia, nationalist, voter