And Then the Earthquake: In Central America, Earthquakes Topple More Than Buildings

On Wednesday, November 7th, a 7.4-magnitude earthquake shook the San Marcos Department along the Guatemalan Pacific Coast. The largest such quake in Guatemala since 1976, the tremors were felt from Mexico D.F. down to San Salvador. International news sources report the death toll at nearly fifty, while hundreds have been displaced, and scores more remain missing. The quake exposed the vulnerable nature of the country’s infrastructure as photos show entire blocks buried beneath debris.

The BBC has reported dozens of seismic aftershocks. However, in this region routinely scared by the Earth’s tremors, the aftershocks often extend beyond the geological sort. On multiple occasions, earthquakes in Central America and Mexico have exposed state weaknesses and have served to shake up the deep-seated political status quo.

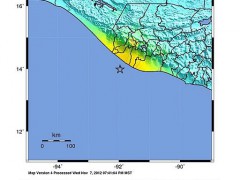

United States Geological Survey ShakeMap. This image is in the public domain because it contains materials that comes from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Consider the 1972 earthquake in Managua, Nicaragua. The quake destroyed 90% of the city, and claimed upwards of 20,000 causalities. To this day, the town’s neighborhoods seem spread out and unconnected. Infrastructure is dilapidated and sporadic.

But the quake not only destroyed the nation’s capital. It also helped lead to the downfall of its longstanding dictatorship. Beginning with Anastasio Somoza’s ascension to the presidency in 1937, the Somoza family dynasty ruled Nicaragua as if it were a private fiefdom. Anastasio parlayed his personal power into ownership positions of successful Nicaraguan businesses. In a country of rampant poverty, the family amassed a fortune valued in the billions of dollars.

Family living in derelict building – Managua, Nicaragua. The huge earthquake that struck Managua in 1972 left between 5000 and 10,000 dead. This photo was taken in 1987. At that time large areas of the city’s centre still hadn’t been rebuilt. Photo taken by Robert Croma and published on Flickr under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

With a National Guard that reported directly to the president, the Somozas used fear and suppression to establish a stranglehold over the nation. Given the Somozas’ support from the United States of America, the family’s perpetual reign may have appeared all but inevitable.

And then came the earthquake.

President Somoza inept and corrupt response helped engender the popular backlash that eventually fomented not only into guerilla warfare, but also a public willingness to challenge the status-quo.

Somoza’s government made little effort to assist the nearly 100,000 affected citizens. The National Guard actually took part in the looting rather than defending against it. Adding insult to injury, President Somoza used his power to manipulate the millions of dollars in global relief that flooded the country. His cohorts would receive emergency supplies at airport and then sell them into the black market for a significant profit.

Managua, after the earthquake in 1972. This image is in the public domain because it contains materials that originally came from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Just as Managua never fully recovered from the 1972 quake, neither did the Somoza dynasty. The rampant corruption cost Somoza support among the nation’s prominent businessmen while international outrage forced the United States to question its allegiance to the dictator. The National Guard’s dereliction of duty helped popular opinion coalesce against the regime that reached critical mass with the outbreak of Civil War in 1979.

Similarly, the 8.0 magnitude earthquake that struck Mexico City on September 19th, 1985, severely shook the national status quo and would eventually leave a six –decade old political system amidst the debris.

For the fifty-five years prior to the earthquake, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) ruled Mexico as a one-party regime. Presidents transferred power every six years through the undemocratic dedazo in which the outgoing president would tap a successor. For decades, the PRI maintained unquestioned power by rewarding party support and discouraging independent civil society.

And then came the earthquake.

Most immediately, the Mexican earthquake underscored the PRI’s bloated inefficiency. The government’s initial response was muddled and unprepared. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs inexplicably denied American offers of aid. As the full toll of the damage became clear, the disaster also revealed the profoundly corrupt nature of the PRI. With over 400 buildings collapsed and more than 3,000 damaged, construction clearly had not met standard building codes, suggesting procedural bribery. Furthermore, the aid that did emerge flowed to PRI supporters while those perceived as the opposition were left figuratively and literally in the dark.

In short the PRI’s inept response to the earthquake displayed a tremendous leadership void. Facing emergency, Mexican citizens united as a civil society to fill this role independent of the PRI, perhaps for the first time in generations. Leaders from the destroyed communities challenged the government’s response, and even refused demands to incorporate their movement into the PRI. Civil society’s demands for a more ‘democratic’ disaster response represented a foundation for inclusive, competitive public policy in Mexico.

The previously feeble Mexican opposition built upon this movement to mount a true challenge to the PRI in the 1988 Presidential Elections. The Institutional Revolutionary Party would in fact hold the Presidency until year 2000 (and they have since returned after a twelve year hiatus with the election of Peña Nieto in 2012). However, the era of one party dominance and minimized civil society was another of many victims of the 1985 earthquake.

What this all means for Guatemala is not immediately clear. Certainly, the devastation in San Marcos pales in comparison to that wrought upon Nicaragua or Mexico. However, this does not mean that the aftershocks will not be felt in Guatemala City. A Pacific region near the Mexican border, San Marcos is key territory for international drug trafficking. The Zeta and Sinaloa cartels have battled for control over the region. Local trafficking networks have emerged, often paid in cocaine as opposed to cash – a paycheck that can only be monetized by introducing the contraband into the local community.

Frustrated citizens may lack only a catalyst to unite their frustrations and to demand more of a weak central government. In 2011, CNA Analysis & Solutions reported that San Marcos had already been converted ‘into a zone of highly motivated citizenry with multiple agendas, some of which have led to situations of protest and social and environmental conflict.’

And then came the earthquake.

Tags: Democratic transitions, earthquakes, Guatemala, Mexico City, Nicaragua, San Marcos